SO IT WAS MID-1965, I was just coming up to my eleventh birthday and I was leaving the kids-stuff comics of DC behind and discovering the wonderful new world of Marvel Comics, masterminded by a cheery bloke called Stan Lee. I had found a character called Captain America that I thought was really cool, with his lack of superpowers, his natty spinning shield and his eye-catching Stars-and-Stripes costume. But it didn't take me long to figure out that this Marvel outfit had other titles and pretty soon, I'd found Fantastic Four and Spider-Man comics as well, and they were just good as the Captain America and The Avengers stories I'd read.

Back in the 1960s, comics companies had no advertising budgets, and there were no comic stores or fanzines or internet to keep customers informed of what other books the company was publishing. If you picked up a Fantastic Four comic and you liked it, the chances were you might be interested in X-Men as well. So the publishers would heavily cross-advertise their various titles in every other comic they published.

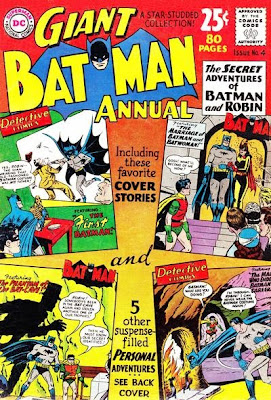

There was no doubt that DC, as the incumbent sales champions and most polished of the comics operations, had the best-looking house ads. Mostly designed by Ira Schnapp, the master letterer of most of DC Comics' covers, the DC ads were an object lesson in grabbing the customer's attention.

|

| Veteran DC editor Mort Weisinger was responsible for the copy, which was mostly pretty corny, but the text was elevated by Ira Schnapp's impeccable sense of comics design. |

Marvel's house ads were quite a bit less polished than DC's, but they did give a pretty good idea of what else was out from Marvel at the same time. Where Weisinger went for a more specialised approach, writing punchy, hard-sell copy, Stan Lee just wanted to bring all Marvel Comics to the attention of all Marvel readers. Every issue.

And here's a confession to horrify everyone ... when I was ten, I was so impressed with the Marvel House ads that I clipped the miniature covers out of those ads with a pair of scissors and kept them as a kind of "Wants List". Yup, I totally vandalised my comics. Many years later, I bought some old Tales to Astonish at auction. The vendor hadn't checked the books carefully and had graded them as fine. But when I received them, you guessed it, some idiot had clipped the cover repros from the Marvel house ads. In the interests of karma, I'd like to think that idiot was my ten-year-old self. I certainly deserved it ...

|

| Maybe Stan's scattershot approach worked, because Marvel's sales rose while DC's were falling - the above ad page is from Daredevil 5. |

At the time, I couldn't know that Marvel Comics had been restricted to a handful of titles, distributed as they were by their own arch-rivals DC Comics. As I described in the last entry in this blog, in 1957 Marvel publisher Martin Goodman had been forced to enter a deal with arch-rivals DC Comics to get his books onto the newsstands. The catch was that DC would only take eight titles a month. Goodman extended his reach by putting out 16 bi-monthly titles, but as he'd been publishing 50-60 titles up to this point, it seriously cramped his style. The restriction eased a little during the early 1960s, but mostly it meant if Goodman wanted to launch a new title, he'd have to cancel an existing one.

However, there was an up side to this restriction. It meant, that Stan was able to advertise just about his whole line of super-hero comics in any one issue of his books, just using two house ads with four covers apiece. This, coupled with Stan's strategy of aggressive and regular guest-starring of a character in another hero's title, meant that the readers very quickly became accustomed to buying the entire Marvel output every month, something you just couldn't afford to do with DC comics.

|

| Wow ... even Millie the Model and the cowboy comics made it into this house ad from Tales to Astonish 66 (Apr 1965). |

It also meant that at least until the mid-Sixties, Stan Lee was able to write just about every Marvel title himself. Which, of course, meant the style and the tone of voice was consistent across the range of product, something that DC with their scores of titles weren't able to manage.

Anyway, it was the advertising policies of, initially, DC Comics and later Marvel Comics that kept me (and no doubt thousands of other kids) informed of what other titles might be in the spinner racks that month. But not always ...

STILL DISCOVERING MARVEL COMICS

In the case of Daredevil, I first stumbled across an issue in a motorway services area. It would have been sometime in the early part of 1965. My family would almost certainly have been on the way to visit relatives in Scotland by car. Back then, not many families had cars and the motorways weren't the giant parking lots they are today.

|

| With this level of traffic, it was no surprise that motorway service areas were a treasure trove of "old" comics. |

So you can imagine how pleased I was to discover a copy of Daredevil 5 (Dec 1964) in the newsagent at one of the few motorway pull-off areas between London and Glasgow. I must have read that issue a dozen times during the remainder of the journey. To my ten-year-old mind, it was a source of wonder that a blind man could be a superhero. And at that moment, Daredevil became one of my favourite Marvel characters - though this early in the game, Stan was still struggling a bit to know what to do with him.

|

| Holidays in Spain were still two or three years away for me in 1965, but a criminal matador was an intriguing concept. |

When I went back and had a look at Daredevil 5, I noticed some indications that perhaps artist Wally Wood was also partly responsible for DD's lack of a clear direction. After floundering for a couple of issues with a revolving door of artists (Bill Everett on issue 1, then a brief run of three with ex-EC artist Joe Orlando), Stan settled on Wally Wood, also an EC alumnus, as the permanent Daredevil artist. But even by this time, Stan had become accustomed to giving his artists the barest outline of the story and leaving the pacing them. That's fine if the artist is Jack Kirby. Even Dick Ayers and Don Heck had been working this way with Stan long enough to know what was required. But Wood was a newcomer to Marvel. He was likely unfamiliar with how Stan would spend as much time on his heroes' private lives as on their action antics. So Wood's pacing was a little off.

Daredevil 5 starts off with a three page action sequence to demonstrate to new readers how the character operates. Then there's a single page with Matt and Foggy in the law office to set up the rest of the plot. Ditko or Kirby would never have restricted this scene to a single page, as Stan needs a bit of room for character exposition. So page 4 looks like this:

|

| Stan tries to squeeze two or three pages of exposition into a single page. |

It's a bit of a car-crash, looking for all the world like one of those EC pages that Wood used to work on where Gaines and Feldstein would have all the dialogue lettered onto the comic page first and make the artists fill in the gaps with drawing. There's more lettering than art here. The rest of the book is a bit better but when Wood got tired of Stan criticising his storytelling, he left Marvel and went to Tower Comics. It wasn't a great loss to Marvel. Much as I love Wood's work - his EC stuff and his Spirit pages are beyond brilliant - he just wasn't cut out for superheroes. As his later work on the Tower books demonstrated.

Another comic I must have picked up in a swap, because it was dated May 1964, was Strange Tales 120. Probably what drew me to the book was the Fantastic Four's Human Torch on the cover, fighting side by side with a human snowman. At this point I hadn't read any X-Men comics, so I didn't really know who Iceman was ...

|

| Fire meets Ice - Jack Kirby's dynamic cover is a cross-over between the Fantastic Four and the X-Men. |

Nice though the Jack Kirby art was in the lead story, it was the back-up story that stayed in my memory. Drawn by Steve Ditko, the Doctor Strange story in this issue was a lot like the short mystery stories that had dominated the title before Stan's super-heroes came along. The plot involves the magician investigating a haunted house, which was very close to home for my ten year old self. In south-east London where I grew up, we were surrounded by bombed out and derelict houses that still hadn't been demolished in the post-war years. More than one of them had a history of haunting attached to them by the kids in the area.

|

| Doctor Strange heroic battles the mystic forces of the haunted house only to discover its horrifying secret ... |

So on that level, I had a real and emotional attachment to this story. The pay-off, which owed a lot to the formula Lee had developed earlier on the monster and ghost tales he did with Steve Ditko in Amazing (Adult) Fantasy, was at the time genuinely creepy. The shock ending is that the house isn't haunted at all. It's that the house itself is a sentient being.

|

| ... the house is alive and malevolent. And only Doctor Strange has the power to force it to release its human captives. |

It probably seems pretty corny now, but in 1965, I can tell you, it scared the bejabbers out of me and my pals. We didn't go near a derelict house for weeks after that story.

Thinking back on this tale and relying on my memory, I was sure that this was the first or second Doctor Strange story, as it featured none of Strange's main foes or supporting cast. I remembered that there were a few Strange stories before Marvel revealed how he became a magician, and my faulty recall was telling me that the Nightmare and the Baron Mordo stories came later. So I looked for this story around issue 111 of Strange Tales. Funny how the memory can plays tricks on you ...

Doctor Strange was to become one of my favourite characters and would remain so until the present day. At his best illustrated by Steve Ditko's art, subsequent artists like Gene Colan and Frank Brunner did the character no disservice at all, and I still remember the later run written by Steve Englehart with reverence.

Another "vintage" item I stumbled across right at the beginning of my conversion to Marvel was Tales to Astonish 39 (Jan 1963). I'd already seen a later Astonish, featuring Giant Man battling the Human Top, the year before, but this one was a really old comic, in my eyes. The cover was very much part of Stan's plan to stay below the radar of DC's distributors by resembling one of early Marvel's standard monster books. The giant red insect dominates the scene with the "Astonishing" Ant-Man in the foreground, but very tiny - an occupational hazard for ant-men.

|

| This doesn't look remotely like a superhero comic - which is probably what Stan intended. |

The plot wasn't really much different from those pre-hero monster tales. The Beetle is zapped with radio-activity, and gets intelligence. The growing really huge bit is when the creature snatches Ant-Man's growth gas and uses it all to make himself man-sized. Ant-Man is then stuck at his tiny size until he can defeat the Scarlet Beetle. But here and there in the story are the first signs of Stan showing you that the world may not idolise and trust super-heroes just because they're super-heroes. Where Batman and Superman would have police officers saluting them and politicians asking them to sort out some problem, in Stan's Marvel universe, the heroes would have no automatic endorsement from either the authorities or the public. In this story, the police speculate that Ant-Man is too frightened to tackle the growing insect problem.

|

| Taking Ant-Man's gas-cylinders, the Scarlet Beetle chucks our hero down a hole and sets off to cause mayhem among the humans ... |

And when the menace is defeated, because they don't know of Ant-Man's involvement, the police wonder why there was no sign of Ant-Man. Of course the readers know that Ant-Man saved the day and the story also shows us that a True Hero doesn't wait around to take a bow ... already Stan's own moral values were coming out in his stories.

|

| Restored to his normal size, Dr Henry Pym sets the little beetle free to live out the rest of his several-week lifespan, while the cops wonder why Ant-Man never showed up to do their job for them ... |

Strangely, Ant-Man didn't really catch on. Stan's reasoning must have been, small boys love insects so here's a hero that works with the insects to battle commie spies and catch crooks. And that's quite sound reasoning. But it was right at the beginning of Lee's hero revolution and Ant-Man was an early experiment that didn't work. It even took me a while to connect the dots and realise that the Giant Man in issue 15 of The Avengers was the same character as the guy who fought the Scarlet Beetle. Eventually, Stan's search for the ideal comic book style would pay off, but that was still a way in the Tales to Astonish 39's future. In the meantime, I had more new Marvel characters to discover. Just round the corner were The X-Men and The Mighty Thor, both visualised by the equally mighty Jack Kirby.

Next: From Explorer to Fan to Collector