Last time on this blog I looked at the lower half of my top ten most fondly-remembered DC stories of my formative years - around 1963 to 1965 - then ran out of room (and time) because I found I had more to say than I'd thought ... so here, then, are the top five. Again, I stress these are not the "best" DC comics of that era, just the ones that struck a chord with me and that I still remember to this day.

5. JUSTICE LEAGUE 21 & 22

OK, maybe this DC story is one of the best of the era. It was so successful that it became an annual event and established the whole DC multiple-universe thing. In the story it's explained that the Golden Age DC characters from the 1940s actually exist in a parallel universe on Earth-Two. The Silver Age DC superheroes all live on Earth-One. OK, it's a tad more complicated than that, as Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman continued straight on from the 1940s to the 1960s, but if you need to know more about that, you can Google it yourself.For me, the first glimpse I had of DC's alternate Earths - and indeed of Golden Age characters - was in the Justice League of America stories, "Crisis on Earth-One" and "Crisis on Earth-Two" in issues 21 and 21 (Aug & Sep 1963) of that comic. And despite the spotty distribution we had to deal with in the UK, I distinctly remember buying both issues from a spinner rack at the same time, probably in the autumn or winter of 1963. Then I pretty much read them to pieces ...

The plot is a little complex, but scripter Gardner Fox has fifty pages for explanations. Essentially, two trios of criminals, from two different Earths, plan to commit crimes then escape justice by immediately fleeing to the alternative Earth. So Earth-One's Felix Faust (from JLA 10, Mar 1962), Chronos (from The Atom 3, Oct 1962) and Doctor Alchemy (from Showcase 13, Mar 1958 - though he was "Mr Element" back then) conspire to commit crimes on their native Earth-One then hide out on Earth-Two ... while The Fiddler (All-Flash 32, Dec 1947), The Wizard (from All-Star 34, Apr 1947) and The Icicle (from All-American 90, Oct 1947) will carry out million-dollar robberies on Earth-Two then cross over to Earth-One to escape. Then, to further complicate things, the Earth-Two villains plan to disguise themselves as their Earth-One allies, rob Las Vegas (called "Casino Town" in the story) and defeat Earth-One's Justice League heroes.

Highlights of Justice League 21 for me were the two scenes in Chapter Two where the "weaker" heroes save their more powerful colleagues. The Atom rescues Martian Manhunter from a shower of fiery pebbles by literally kicking them into touch, while Green Arrow saves Superman from a fire hydrant transformed into Kryptonite by dowsing it in lead paint from a well-placed trick arrow. I also loved the scene where the JLS summons the JSA with a good, old-fashioned seance ... and the following iconic scene where the Justice League members shake hands with their Earth-Two counterparts. All magical memories for me, even after more than fifty years.

The issue ends with the JLA, trapped in their own secret sanctuary by the magic of The Wizard, escaping to Earth-Two via Dr Fate's magic and preparing to chase down the Earth-One villains there.

So complicated is this tale that the splash page of Justice League 22 is given over almost entirely to a recap of the story so far. It's exactly the sort of thing I would have skipped over as a nine-year old. But here is is, in case you really need to read it.

There then follows an epic 17-page battle as the combined might of the Justice League and the Justice Society defeat their foes, one-by-one. And just when it seems their victory is complete, the superheroes are trapped by another of the villain's machinations, this time ending up floating in space, trapped in cells tailor-made to negate their powers. Of course, our heroes escape in a cunning and clever way and congregate on Earth-One to beat the tar out of the cross-dimensional baddies in an epic double-page spread by Sekowsky and Sachs.

Much as I love this comic - and bear in mind this is regarded as a classic by many Silver Age fans - there's not really a great deal of story here. An incredible 35 pages of the 50-page tale is devoted to battle scenes. More than two thirds. With a few chat scenes interspersed. It's no wonder that later fans criticised the Justice League of America comic for portraying the DC heroes as having scant personality and interchangeable dialogue.

Stan Lee's more populist approach in the Marvel Comics of the same period would very quickly start stealing sales from DC, while the DC editors scratched their heads and wondered why.

I don't think Gardner Fox and his DC contemporaries were bad writers, but they were of another era. And what was sufficient back in the 1940s Golden Age of Comics just didn't fly in the youth-culture driven 1960s, something I've discussed in other chapters of this blog. A cool name, costume and clever super-powers weren't enough, on their own, to sell comics. The new breed of comic fan wanted characterisation, wisecracks and a good storyline as well. And that's what, in the end, drove me away from DC and towards Marvel.

But hokey though they may be ... my nine-year old self still loves those old Justice League comics ...

4. BATMAN ANNUAL 4

This was one of the earliest American comics I can remember owning. It certainly wasn't bought new - it was coverless - and I wasn't one of those kids who likes to rip the covers off comics. I have a feeling someone might have given it to me, because the cover was missing. But wherever I got it from, I loved this comic, literally to pieces.Two stories in the bumper crop of Batman reprints from the character's silliest period still stand out in my memory... "The First Batman", in which Batman discovers his father fought crime in a bat-costume before he did, and "The Man Who Ended Batman's Career" in which Batman develops bat-phobia and changes his identity to Starman. So much did I love the latter story that, when I was nine, I tried to make myself a Starman costume, so I could help Batman.

"The First Batman" originally appeared in Detective Comics 235 (Sep 1956), story by Bill Finger and art by Sheldon Moldoff and Stan Kaye, though the first page carries Bob Kane's signature. The story recaps the origin of Batman and reveals the final fate of Joey Chill, the murderer of Bruce Wayne's parents. But a chance discovery of a Batman-like costume in the attic of stately Wayne Manor prompts Bruce to recall the time when his father wore a Bat-costume. Attending a masquerade ball in the costume, Wayne senior is grabbed by gangsters who need his medical skills to remove a bullet from crook Lew Moxon. Dr Wayne fights back though, and Moxon is arrested and sentenced to ten years. When Moxon is finally released, he wants to get even, but isn't prepared to kill Dr Wayne himself. Thus it's revealed that Joey Chill was only the trigger-man. It's Moxon who was behind the murder of Bruce Wayne's parents. The rest of the tale has Batman track down Moxon and ring a confession out of him.

It's a memorable tale for me because it reveals essential back story to Batman's origin. I don't know whether those plot details became canon ... I suspect not, but I quite like the way Bill Finger revises Batman's history in an interesting way.

The second memorable tale in that Annual was "The Man Who Ended Batman's Career", which appeared originally in Detective Comics 247 (Sep1957). Another Finger/Moldoff extravaganza, this time inked by Charles Paris, this story had Batman afflicted with a morbid fear of bats by mad Professor Milo. Unable to even look at the emblem on his Batman costume, Bruce Wayne is forced to adopt a new costumed identity ... Starman. Starman's gimmick is that he can fling ninja stars with deadly accuracy. Only Robin's intervention gets Batman over his phobia and back to his bat-fighting self.

Of course, the crooks soon figure out that Starman is just Batman in another costume ... but it was a fun ride while it lasted, and my nine-year old self was disappointed that Starman didn't get his own comic. Plus, I knew about ninja stars long before anyone else did.

What I had completely forgotten about Batman Annual 4 was that it also reprinted the first appearance of Batwoman. Now anyone who has followed my blog over the years will know that my favourite female comic characters typically have dark hair. So as a kid, I loved the 1950s version of Batwoman and thought she was a wonderful partner for Batman ... much better than that daft Robin.

Of course, given the times, Batwoman was portrayed as a "typical female". Her Bat-weapons were sneezing face powder, charm bracelets that doubled as handcuffs and a compact mirror she used to dazzle crooks, all carried in a handbag ... At one point, when Batwoman tries to help, Batman observes, "This is no place for a girl". A few pages later, some crooks say, "Batman and Robin ... and Batwoman. There's only two of them, the girl doesn't count." Finally, Batman figures out her secret identity as Kathy Kane, trapeze artist-turned-socialite, and tells to end her career as a crimefighter. "If I found you out," says Batman, "crooks could too, eventually! Once they learned your real identity, you'd be in mortal danger." Batwoman capitulates. "I never thought of that," she says, "I guess you're right. I - I'll quit my career as Batwoman." Thank goodness she didn't, eh?

I'll round out this section with a selection of my favourite Batwoman covers, ranging from her second appearance in Batman 105 (Feb 1957) to her final outing in Detective Comics 318 (July 1956).

3. SUPERBOY 89

Another comic I really enjoyed as a pre-Marvel child was Superboy. Incredibly, there are no collected editions of the Silver Age Superboy stories. I can't only surmise that there some sort of rights problem that prevents it. However, The Legion of Superheroes collections from DC include many stories from the original Superboy comics, including one of my favourites, "Superboy's Big Brother" from Superboy 89 (Jun 1961).My earliest exposure to Superboy would likely have been through one of those old black-and-white Superboy Annuals that were published in the UK during the late 1950s and early 1960s. I definitely recall having an Annual that had about 80 pages of George Papp-drawn Superboy reprints with Rex the Wonder Dog as a backup, but I can't identify which one it was because it was coverless. And I can't rightly say whether I read "Superboy's Big Brother" in the colour comic or in the B&W reprint, but the story stuck with me over the decades ...

Written by Robert Bernstein and drawn by George Papp, behind a cover by Curt Swan and Stan Kaye, "Superboy's Big Brother" was a rare, 19-page tale at a time when DC typically filled their books with eight and 13-page stories. And it's probably Bernstein's highest-profile story.

The tale begins when a mysterious rocket crash-lands near Smallville. Superboy investigates and discovers a lad slightly older than himself among the wreckage. The teenager has no memory of who he is, but a plaque round his neck inscribed with Krytonian characters. Superboy immediately assumes that the newcomer is Kryptonian and probably related. This is confirmed when "Mon-El" proves to have super-powers, just like Superboy. However, further discoveries - Krypto doesn't recognise Mon-El and Mon-El is immune to Kryptonite - make Superboy suspect there's another explanation for his brother being on Earth.

As Superboy's suspicions grow, he lays a trap for Mon-El and disguises some lead boulders to look like Kryptonite and arranges to have them rain down on Mon-El and himself. Superboy pretends the "Kryptonite" is killing him, and when Mon-El appears to have the same reaction, Superboy thinks he's exposed Mon-El's deception. But it turns out there's an explanation.

"Mon-El" is actually from the planet Daxam, where the inhabitants are super-sensitive to lead, a substance that kills them with only one exposure. Superboy's only recourse is to send Mon-El into the Phantom Zone until a cure for the lead poisoning can be found.

It's a story full of loss, loneliness and recrimination, a rare emotions-driven story in DC's Silver Age. Superboy's feeling of isolation - as the last survivor of Krypton - makes him ready to accept Mon-El as his older brother. Mon-El is also a connection to Superboy's lost parents, and as a teenager rather than a grown man, Superboy would still feel that loss keenly. And it is Superboy's suspicions that cause him to lay the fatal trap for Mon-El, dooming his best friend because he thought Mon-El was trying to cheat him.

All these story elements I recognised as important and resonant, even as a nine-year old child. Even back then, I was looking for stories about human emotions, something that most of the DC line didn't offer.

Of course, later - probably due to reader reaction - a cure was found for Mon-El and he was able to join the Legion of Superheroes in the 30th century. But it was this story that started it all and still remains in my memory more than fifty years after I first read it.

2. ACTION COMICS 300

My second-favourite DC comic of my pre-Marvel years is another Mort Weisinger spectacular, "Superman under the Red Sun", which appeared in Action Comics 300 (May 1963).Though only running 14 pages, this story - written by Ed Hamilton and drawn by Al Plastino - was able to give us a sense of Superman's isolation as a stranger in a strange land.

It starts with Superman investigating a spaceship in Earth orbit, which turns of to be a craft of the criminal organisation, The Superman Revenge Squad. The spaceship tries to flee, going so fast it cracks the time barrier into the future. Superman gives chase, but suddenly loses his powers and plummets to earth, a million years in the future under a red sun.

Though Mort Weisinger (along with Julius Schwartz) came from a science fiction background, the science here is wobbly. A star like Sol may have started as a red dwarf, and later in its cycle might become a white dwarf, but it doesn't have enough mass to end up as a red giant. So in the far flung future, Sol wouldn't become red. Plus, a million years is but a moment in a star's evolution. It would take around 10 trillion years for a star like Sol to enter its next phase. But I didn't know that when I was nine.

The main point is that Superman finds himself alone and powerless a million years in the future where all his friends are long-dead. Using only his wits he must figure out how to escape from this time and return to 1963. Accompanied only by an android duplicate of Perry White, Superman sets off to reach his Fortress of Solitude at the North Pole, where he believes he may find a way to escape his predicament.

Along the way, Superman and Robo-Perry encounter some exotic life forms, like a land whale and land octopi (which again wouldn't have evolved in a mere one million years), which add some further danger to the trek.

Finally, Superman makes to the Arctic, now a desert wasteland, and scales the cliff to the door of his Fortress. But even as Superman gains entry through the door's huge keyhole, he's dismayed to discover that the bottle cit of Kandor is no longer there. I'm not quite sure how that would have helped him, but there's another solution at hand. A miniature Kandorian rocket has been left behind, along with the shrinking ray Superman has used before to reduce his size to allow him to enter Kandor. So that's all fine. He can make himself small enough to climb in the rocket and fly out of there and through the time barrier. But then the plotting gets a little muddled.

Superman also finds a piece of Red Kryptonite he was looking for, thinking "This Red Kryptonite won't affect me till I unwrap it. I once observed its effect on Krypto and it should have the same effect on me." What? What effect? The second to last panel has tiny Superman back in Metropolis musing, "Now to wait until the temporary effect of the Red Kryptonite wears off and I'm my super-self again."

I suspect some incompetent editorial interference. Perhaps some panels were removed from the last page to accomodate the ad. But there's definitely something missing here. Perhaps the original script had Superman shrunk down by the Red Kryptonite. That's certainly the implication in the published text. Maybe Weisinger thought that Red K shouldn't affect Superman when he doesn't have powers, so asked his staff to edit that bit out. They just didn't do it properly.

That notwithstanding ... it's still one of my all-time favourite early 1960s DC stories. It has a melancholy feel to it that other Superman stories of the era didn't have.

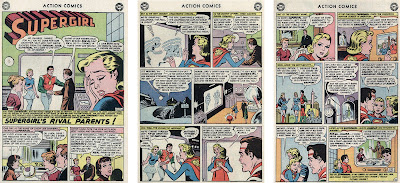

1. ACTION COMICS 309-310

My top DC story of the early 1960s is another sad one. "The Untold Story of Argo City" is an expanded version of the origin of Supergirl that appeared back in Action Comics 252 (May 1959). Essentially, the plot points are the same, but the later two-parter, which ran in Action Comics 309 and 310 (Feb-Mar 1964), expands more on the scenes in the doomed Argo City, where the Kryptonians struggle to survive life on a rock of solid Kryptonite.The story is scripted by Leo Dorfman - expanding the original plot of Action 252 by Otto Binder - and drawn by Jim Mooney, and begins with Linda (Supergirl) Danvers dreaming that her real parents, Zor-El and Allura, are trying to communicate with her. With the help of Superhorse's telepathic powers, Supergirl is led to believe that her Kryptonian parents are alive but trapped in the Phantom Zone. Yet when Supergirl enters The Zone she fails to find any trace of her parents.

|

| Via the ChronoScope, Supergirl can watch the last moments of Argo City, as first survival then doom beckon to the last surviving citizens of Krypton. |

Supergirl's quest takes her first to Kandor City, where scientist help track the movements of Supergirl's parents inside the Survival Zone to the implauible "New Krypton", a memorial set up by Superman and Supergirl in tribute to the lost souls of Krypton. From there she then unnecessarily follows the Survival Zone "gulf stream" back to Earth where she can begin the process of extraction using a handy "sensitive view screen for national defence" that's conveniently stowed in the Danvers' basement. A few tweaks and Zor-El and Allura are able to step through the screen and into Supergirl's reality.

But after a few joyous scenes of reunion and enjoying each other's company, it's plain that this can't be allowed to go on, so the Els must be sent to Kandor by DC's Dark Overlord Weisinger so that the status quo can be maintained.

I think the reason I still remember this story and how it made me feel when I read it back in 1964 is that once again, it's about emotions. Supergirl's feeling of loss when she believes her real parents are dead, her feeling of hope when it seems possible that they have somehow survived, then the emotional dilemma she faces if her real parents and adoptive parents are living in the same world. I also found the scenes of the Argoans trying to survive quite affecting, especially the scenes of hopelessness when the meteor shower pierces the protective lead sheeting, exposing the Argo citizens to the deadly Kryptonite rays ...

To me, this all demonstrates that the stories that resonate with us and stay with us even decades later are always powered by emotion. I think this was something that Stan realised when he first started trying to craft better stories at Marvel. When DC published the occasional emotion-driven story it was by accident and even as Marvel began to outsell DC in the mid-1960s, the DC editors never made the connection, and continued to stick to their plot-driven tales for the rest of the decade, allowing Marvel to take the top spot and relegate the once mighty DC Comics to second place.

One final coda ... Action Comics 309 also featured a Superman story where the tv show "Our American Heroes" wants to honour Superman, but as Superman's "best friend" Clark Kent is also on the guest list, Superman's in a bit of a bind. One by one, his solutions are removed until it seems like his identity will be compromised by Clark Kent's "no-show". Then - surprise - Clark shows up. How did he do it? The answer seems so obvious now, leading to one of the greatest final lines in a comic story ever ...

Next: Of Marvel, Magic and Strange Tales

The thing about DC stories of that era is that you're gonna like them for their nostalgia value (if you read them as a kid), quite regardless of how good, bad, or indifferent the stories were, whereas, with Marvel, though the nostalgia aspect still applies, you're also gonna like them because they were good. (Hey, I can speak American.)

ReplyDeleteThat's exactly my point, GR ... I wanted to write specifically about the DC stories that I still remember after all these years, not because the script were great or the artwork was memorable, but because I can still recall how they made feel, over fifty years later.

DeleteAlso, I couldn't really write about the best DC Comics here, because this is a Marvel blog :-)

DeleteEven though I was a big Marvel fan, there were a lot of DC Comics that I loved. Back in the earlier Comic Conventions, I was able to meet many of the best artists and writers of the Silver and Golden ages and was treated so nicely by the people from both companies, I would never have a negative word to say about any of them!

ReplyDeleteI got to meet many Marvel legends through working for Marvel UK during the 1980s, but I never got meet any of the DC people, like you did. So I envy you that ...

Delete