A YEAR ON FROM THE GREAT MARVEL EXPLOSION OF 1968 and it was becoming noticeable that Martin Goodman's grand plan to increase Marvel's output wasn't going to be sustainable.

When Marvel's total monthly page output went up from around 280 pages per month to about 400 pages, Editor Stan Lee needed to find more creators to produce the extra 120 pages of original story art he'd need just to keep the Marvel machine fed. He already had Roy Thomas and Gary Friedrich helping out on scripting. He'd added Archie Goodwin and Arnold Drake in 1968 - both looked great on paper, Goodwin with long experience at Warren magazines and Drake with a wealth of experience at DC, but by mid-1969, Drake had left Marvel and Captain Marvel needed a new writer.

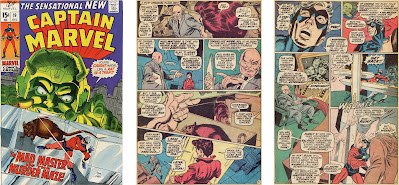

As it turned out, Gary Friedrich was able to step in for a few issues, while editor Stan cast around for a permanent replacement. Also incoming was new Marvel recruit, Frank Springer, replacing Dick Ayers who'd pencilled the last couple of issues. Springer had pencilled at Dell until the end of 1967, then joined DC for about eight months - I'd particularly enjoyed his work on Secret Six - before hopping over to Marvel to draw SHIELD 4 (Sep 1968).

Captain Marvel 13 (May 1969) kind of re-hashes issue 12, with an unnecessary second battle against the Manslayer and a punch-up between Mar-Vell and Yon-Rogg. Incredibly, Yon-Rogg knocks Mar-Vell down during the fight, despite Captain Marvel's hugely enhanced physical strength (courtesy of the cosmic entity Zo). It's almost as if Friedrich hadn't read the previous issue. Or maybe he was just dialoguing an Arnold Drake plot ... either way, it added up to an unmemorable story.

|

| Although touted as a crossover with Avengers 64 and Sub-Mariner 14, Iron Man's appearance in this issue of Captain Marvel seemed more like marketing opportunity than a story necessity. |

Captain Marvel 14 (Jun 1969) featured a guest-appearance by Iron Man, a sure sign that sales on Mar-Vell's book weren't all that Editor Stan Lee had been hoping for. But this shouldn't have been much of surprise for Stan. Both art and scripts on the title had been distinctly second-tier up till this point ... and something had to be done. The introduction of Iron Man didn't make a great deal of sense, as guest villain. The Puppet Master (not looking like a ventriloquist's dummy any more, he had plastic surgery in Strange Tales 133, Jun 1965) takes possession of Iron Man and forces him to seek out and battle Captain Marvel for no reason that is ever explained.

But for me, now as then, the plot ("Captain Marvel battles Iron Man") is the least important part. The character development has always been more interesting to me. This issue moves it forward a little. Captain Marvel returns to the orbiting Kree ship and has a showdown with Yon Rogg - though Mar-Vell inexplicably allows his enemy to live - and then Zo decides Mar-Vell has had enough freedom and must now return to the Kree homeworld, for reasons yet to be explained.

And that's exactly what happens in Captain Marvel 15 (Aug 1969). Working with incoming newcomer Tom Sutton, Gary Friedrich takes Mar-Vell off in a far more cosmic direction. It's almost a foretaste of what Jim Starlin would do with the character just a few years later. Zo begins by showing Mar-Vell his past and his future, revealing that Mar-Vell is destined to destroy his own people. Unable to accept that his fate is inevitable, Mar-Vell resolves to follow the path set out by Zo but plans to thwart Zo's predictions at the first opportunity. When he does arrive on the Kree homeworld, he's embroiled in a battle against the invading followers of Tam-Bor.

I quite like Sutton's groovy, cosmic layouts here, but you can see that his draftsmanship isn't quite as slick as more seasoned artists like his predecessors Dick Ayers and Frank Springer. Even Dan Adkins' usually deft inks can't quite punch this up.

Then, just when it looks like Gary Friedrich is taking this book in an interesting direction, he's replaced by incoming scripter Archie Goodwin, who makes a pretty good fist of tying up all the disparate events and situations created by all the previous scripters on the series.

|

| Captain Marvel 16 (Sep 1969) is a complicated issue, as Goodwin tries to sort out and make sense of the various plot threads dangling since the beginning of the series. |

So ... it turns out that the Kree Supreme Intelligence (introduced in this issue) is behind almost everything that's happened. Two Kree traitors have been scheming to take over the Kree Empire, second-in-command Zarek - who also posed as cosmic entity Zo - and his henchman Ronan the Accuser. The appointment of Yon-Rogg as Mar-Vell's superior officer was all part of the plot, and Mar-Vell - because he was a straight-arrow hero-type - was selected by Zarek as the fall-guy to blame it all on. Poor Medic Una was just so much collateral damage. The Supreme Intelligence was aware of the plot and simply bided his time till it came to a head, knowing that Mar-Vell would do the right thing. For his heroic actions, Captain Marvel is promoted to warrior and is given a new uniform. And he gets to keep his Zo-given cosmic powers. Yes, some of the resolutions are wobbly, but it's pretty obvious that this is a clearing-of-the-decks for a major change in direction.

It's great to see Heck back on pencils, with some fine finishing by Syd Shores on inks. But it's only for a moment, as next issue, Editor Stan brings in the big guns to try to get the title up on its hind legs, assigning Roy Thomas as scripter and DC Comics stalwart Gil Kane as artist.

WHO THE HECK IS GIL KANE?

Gil Kane (born Eli Katz, 6 Apr 1926) began his career at MLJ (later Archie Comics) in 1942 where he worked in the production department erasing pencils, ruling panel borders and outlining speech balloons. Fired after three weeks, Kane got a job at the Jack Binder Studio doing pencilling work. "They weren't terribly happy with what I was doing. But when I was rehired by MLJ three weeks later, not only did they put me back into the production department and give me an increase, they gave me my first job, which was Inspector Bentley of Scotland Yard in Pep Comics, and then they gave me a whole issue of The Shield and Dusty, one of their leading books," he told The Comics Journal in 1996. By 1944 he was freelancing for Simon and Kirby, who were supplying material to DC, and drawing for other publishers like Hillman, Rural Home and Aviation Press. Kane was drafted into the Army the same year, not returning to civilian life until 1945. He began drawing directly for DC under editor Sheldon Mayer, while contributing art to a range of Prize Comics titles. By 1949 Kane was working on Julius Schwatz's stable of titles, notably Jimmy Wakely, Rex the Wonder Dog and All-Star Western.

|

| Western comics were big sellers for DC during the 1950s and Kane's work was much in demand. Later, he'd also draw sf and romance strips for the company. |

Kane continued at DC throughout the 1950s, drawing anything he was asked to - science fiction, romance and westerns - but as these genres began to flounder, DC was looking for other avenues and turned their attention to superheroes once more.

|

| With the DC superhero revival in full swing, Kane was their star artist on two important books, but even the occasional job on DC mystery titles wasn't enough to fill his schedule. |

Kane got the job of pencilling the revived Green Lantern, but found with the loss of his other titles, he hadn't enough work to keep him busy. "By the end of the '50s, everything began to collapse and, little by little, I lost all of my work," Kane told The Jack Kirby Collector in 1998. "I lost Rex, the Wonder Dog and all the westerns. I lost everything and had nothing going. I would occasionally get a science-fiction story from Julie. I went over to Western/ Gold Key and worked with Russ Heath as a partner for a while; I penciled and he inked. So I picked up work wherever I could. Green Lantern filled in a lot but not completely; it was every six weeks and not a monthly book." Kane pitched a revival of The Atom to DC and began pencilling that, as well. "I designed the character and the costume and everything else, and showed them my drawings and sketches and they decided to build a magazine around it," said Kane in an interview with Comic-Art.com. "It was very much like a character done by my favourite artists Louie Fine and Reed Crandall [Doll Man] ... I must admit that it was sort of boring doing it. I really didn't enjoy it ... because I longed to ink my own pencils, which they wouldn't let me do."

|

| Stan started Gil Kane off on covers, but soon found some interior pencilling for him on The Hulk and Captain America. |

Towards the end of 1966, after trying to get in at Tower Comics, Kane went to Stan Lee and picked up some work pencilling The Hulk in Tales to Astonish, where he was allowed to ink his own work. A month or two later, Kane was also pencilling and inking Captain America in Tales of Suspense. That and some cover work from Stan seemed to help, but Kane's first Marvel tenure only lasted a short while. After about three months, Kane was back at DC.

Maybe the prospect of losing one of their star artists focussed DC's attention and they found him more work, adding regular work on Detective Comics. Throughout 1968 and 1969, Kane was also pencilling on Hawk and Dove, Captain Action, Batman and Teen Titans. The Atom was merged with Hawkman in mid-1968, but Kane didn't draw the new title. Then, in mid-1970, Neal Adams took over the art on Green Lantern, and although Kane drew The Flash for a few months, it was looking like DC were struggling to hang on to Gil Kane.

|

| Gil Kane: 6 Apr 1926 - 31 Jan 2000 |

By mid 1971, Gil Kane was working pretty much exclusively for Marvel, drawing Amazing Spider-Man and most of their covers.

AND BACK TO CAPTAIN MARVEL

Captain Marvel 17, cover dated Oct 1969, was on the newsstands 15 Jul 1969. It was pretty obvious that this was a completely different approach to the character.

|

| The whole idea of a youngster miraculously transforming into a superhero on demand did seem awfully familiar. Rick Jones was even given Billy Batson's signature blue trousers and red top. |

Roy Thomas ditched most of the backstory and re-tooled Marvel's Captain Marvel to vaguely resemble the classic Fawcett version. Rick Jones, former partner of both The Hulk and Captain America, was drafted in as the Billy Batson stand-in. Rick only had to clash his wristbands together to swap places with Captain Marvel in the Negative Zone. And their first order of business is to rescue Carol Danvers, who we saw kidnapped by Yon-Rogg in the previous issue.

The only slight glitch I saw was where Captain Marvel claims that he now has no powers, except for those that the Nega-wristbands give him (Rick's wristbands don't give him any powers). Yet in Captain Marvel 16, Captain Marvel explicitly tells us he retains the power bestowed on him by "Zo". I'm confused ...

But whatever powers Captain Marvel now has, they're not enough to keep Yon-Rogg from making off with his captive, Carol Danvers. And hot on his trail ... Rick Jones.

Captain Marvel 18 (Nov 1969) takes a little time to get going. First there's an unexplained incident where Rick Jones is nearly run over by a random motorist. Then there's a strange sequence at a diner in a nearby town where Rick sings a song, gets into a bar-fight and is offered a recording contract by Mordecai P. Boggs. Captain Marvel then "deduces" where Yon-Rogg is hanging out, though no explanation is ever given as to how he did it. The confrontation with Mar-Vell's mortal enemy is drawn by John Buscema, and during the fracas Carol Danvers is exposed to radiation from a Kree Psyche-Magnitron ... this is important because this is what causes the genetic transformation that allows Carol to gain super-powers and become Ms (later, Captain) Marvel.

|

| Captain Marvel is at the mercy of a mad sociologist, trapped in a death-trap apartment block with hundreds of terrified tenants. Not your usual superhero tale. |

The following month, Captain Marvel 19 (Dec 1969) finally gave us a story that wasn't just tying up loose ends from previous issues and setting the scene for this new version of Mar-Vell. Rick Jones needs a job and somewhere to live and answers an ad in The Daily Bugle offering accommodation in a luxury high-rise. But the landlord Cornelius Webb is a crazed sociologist who wants test the work of behavourist Burrhus Skinner to see if humans can be conditioned in the same way that rats can. As Webb conjures up illusions and deadly physical traps, Captain Marvel tries to protect the tenants while finding and stopping Webb. But it's Auschwitz survivor, the kindly Mr Weiss, who literally pulls the plug on Webb and causes his downfall.

It's a little heavy-handed in places, but it does seem to be a genuine attempt to offer a slightly different take on Marvel's usual super-hero tale. The letters page of the issue reveals that the plot came from Gil Kane. And though there's no advance warning on this issue's letters page, the title would be going on hiatus for six months, though no reason was ever given.

When Captain Marvel did return in late March 1970, it was the same creative team and the story picked up without a blip. Rick and Mar-Vell decide that the one person who can help them both out of the Negative Zone trap is Dr Bruce Banner, and the pair resolve to track him down. There is a side plot with some organised looters taking advantage of a natural disaster, but the main part of the tale is the inevitable collision with The Hulk.

There's still no satisfying explanation given by Marvel for just why the title went on a break. On the letters page, Roy insisted that the last few issues were "sales blockbusters" (really, Roy?) ... but it doesn't seem terribly likely that Marvel would suspend a successful title on a whim.

Also, I don't think it likely that Gil Kane sat around waiting for Captain Marvel to start up again. My guess would be that all the Kane issues were drawn at the same time and the art to Captain Marvel just sat in a drawer until they were ready to publish it.

Captain Marvel 21 (Aug 1970) would signal the swansong of the title for a while. The entire issue is pretty much a battle royale with the mighty Hulk. Mar-Vell is outmatched from the get-go and the fighting only comes to an end when Rick returns to our universe and confronts The Hulk. Some part of the monster remembers his young friend and the creature's anger evaporates ...

The idea of asking for Banner's help in freeing Captain Marvel from the Negative Zone is left unresolved - deliberately according to Roy Thomas' comment in the issue's letter column - so there wouldn't be a change to the concept of Rick Jones and Mar-Vell trading atoms in the immediate future.

|

| Marvel kept Captain Marvel in front of readers by making him an important player in the classic Kree-Skrull war storyline in The Avengers ... much of it drawn by superstar artist Neal Adams. |

Roy Thomas wasn't about to give up on Captain Marvel ... he reintroduced the character in a pivotal role in the Kree-Skrull war that would play out in The Avengers from issue 89 (Jun 1971) to 97 (Mar 1972). This would give Marvel the confidence to re-start the Captain Marvel title a couple of months later with Thomas editing Gerry Conway on script and veteran Superman artist Wayne Boring on pencils.

In the haitus, though, DC Comics must have sensed an opportunity. Thinking Marvel's Captain Marvel gone for good - at least in his own title - they entered into a licensing agreement with Fawcett to start publishing a new Captain Marvel comic, on sale just before Christmas 1972, and managed to get the original creator C. C. Beck out of retirement to draw the book. Marvel got wind of their plans and made sure DC didn't nurse any notions of calling the book "Captain Marvel". So DC titled the comic Shazam, and used the Captain Marvel name smaller on the cover. On paper it might have seemed like a great workaround, but Marvel hit DC with a cease and desist order pretty promptly and though the litigation dragged on a bit, by Shazam 14 (Nov 1973), DC were forced to remove the "Original Captain Marvel" sub-line from the Shazam covers.

|

| I'm not sure what DC were thinking ... the project feels more like a spoiler than a serious attempt to revive a character whose time was up two decades earlier. |

Meanwhile, back at Marvel's Captain Marvel book, it was just more of the same with a not-great storyline and art from a skilled but ultimately unsuitable artist. If Marvel was going to make a go of Marvel, something drastic had to happen. Fortunately, a newcomer, Jim Starlin was just a couple of months way from making his debut pencilling the series, then plotting and finally writing and drawing the whole thing himself. He brought his Thanos character with him and that run was to set the character up for a hugely successful six-year run in his own title and numerous spinoffs, including making Carol Danvers a superhero, first as Ms Marvel, then as Captain Marvel in her own right.

|

| Now it gets good ... Jim Starlin brought a fresh and different take to the character of Captain Marvel and pretty much made it his own. |

But that all took place in the Bronze Age of Marvel Comics and is a subject for another time ... and probably another blog.

Next: Classical Art and Comic Covers

Nice post with a good selection of images. I'm glad I didn't delete my bookmark during your hiatus! A few quibbles. Simon and Kirby were not supplying art to Martin Goodman in 1944. Their last work on Captain America hit newstands in the fall of 1941 and must have been prepared around the late summer of that year. After leaving Goodman they worked for National Comics, and by 1944 Kirby was serving in Patton's Third Army. The young Kane did work for Simon and Kirby, but it must have been for National. Also, I doubt that any litigation was commenced to force DC to drop references to Captain Marvel on the Shazam covers. These disputes are almost always handled with an informal cease-and-desist letter rather then with a court order.

ReplyDeleteGood point ... Simon and Kirby were supplying material to DC by that time ... I'll edit the post to reflect that. Thanks for the catch.

DeleteGood to see this site up and running again!

ReplyDeleteI know I'm a bit late to this party, but about Captain Marvel #20-21: during the hiatus after #19 (sometime in mid-1970), Marvel started running half page ads at the bottom of pages 12 and 13 (thus turning 19 pages of art into an apparent 20-page count). So, if Kane had actually drawn these issues around the same time as #19 (in late 1969), he would have had to do a bit of reworking to make the story fit into this new format. Not that it couldn't have happened as you suggested, but it's an argument in favor of #20-21 actually being done in mid 1970 rather than late 1969.