When Iron Man, Giant-Man and The Wasp decided they needed a break - after the epic war against Zemo and his "Masters of Evil" in Avengers 15 & 16 (Apr - May 1965) - the founding Avengers recruited ex-villains Hawkeye, Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch as replacements then departed, leaving Captain America in charge, a role that was never sought but rather thrust upon him.

|

| It's all smiles in the final panel of Avengers 16, but challenging times would lie ahead for Captain America and the small band of former super-villains that now made up The Avengers. |

Kang the Conqueror had first battled the Fantastic Four, back in FF19 (Oct 1963), in the guise of the bogus Pharaoh, Rama-Tut. Though at this point "Rama-Tut" admitted he was from the 25th Century, he didn't reveal his true identity. Even in his second substantial appearance in Fantastic Four Annual 2 (on sale, 2 Jul 1964), when he rescued Dr Doom from an eternity of floating helplessly in space, the pair speculated that they were related, or possibly the same individual.

It wasn't until his appearance as Kang the Conquerer in Avengers 8 (Sep 1964 - on sale, 7 Jul 1964), that the true picture began to form. After his encounter with Doom in the 20th century, "Rama-Tut" tried to return to the year 3000, but overshot and crash-landed in the year 4000. He quickly took control of this savage, desolate future and became overlord of the warring tribes. Quickly tiring of ruling these war-ravaged lands, he resolved to travel back to the 20th century and conquer a cleaner, greener world.

There's a couple of small problems with this scenario. The first and most glaring error is that it's highly unlikely that Kang's ancestor/alter-ego Dr Doom would sit idly by while Kang tried to subdue a contemporary Earth. After all, ruling the world is top of Doom's bucket list. The second is it's quite extraordinary that Kang would travel back to invade our era without at least an honour guard of his future barbarians. You'd have thought his ego would have demanded it.

It proved to be his undoing as, alone, he turned out to be no match for The Avengers and, his weapons ineffective and his battlesuit in tatters, he was forced to flee back to the future. A few months later he would concoct a cockamamy plan to defeat the team in Avengers 11 (Dec 1964) with a robot of Spider-Man. Stan missed a trick here by not emphasising that robots were also a specialty of Dr Doom, thus reinforcing the link between the two, but it's just a minor niggle. What Kang needed was a far more epic vengeance plan, worthy of the character's potential.

All of this brings us to the return of Kang in Avengers 23 & 24 (Dec 1965 & Jan 1966). Issue 23 opens with the three remaining Avengers bickering among themselves, but mostly blaming Hawkeye for driving Captain America away. We get a quick glimpse of Cap, in his Steve Rogers identity, getting himself a job as a training partner for a boxing champion in upstate New York. But while that's going on, Kang is laying his plans to strike once again at The Avengers. Believing the team are at their most vulnerable without the leadership of Captain America, Kang decides now is the time to strike and lays a trap to abduct Hawkeye, Quicksilver and Scarlett Witch. The plan does sound a slightly odd note in that Kang doesn't remark that these Avengers have done him no personal injury. It was Thor, Iron Man and Giant-Man - along with Cap - who thwarted his plans twice before.

Nonetheless, the three newest Avengers are trapped and dragged unconscious into Kang's future, where they're placed in giant specimen jars as bait to lure Captain America into a snare. Next we meet Princess Ravonna, whose kingdom is targeted for conquest by Kang. The despot has offered to reprieve her land if the Princess will only agree to marry him. Meanwhile, back in the 20th century, Cap hears that The Avengers are missing and races to help. Unaware that aid is on the way, the three captured Avengers escape their glass prisons through Wanda's hex power and give battle to Kang's soldiers. Hawkeye and Scarlet Witch are quickly recaptured. Only Quicksilver escapes to continue the fight. And it's then that Captain America reaches the Avengers Mansion and issues a challenge to Kang.

With Ravonna overhearing Cap's challenge, Kang has no choice but to accept and brings Cap into the future. Though he initially beats Cap and Pietro, Hawkeye and Scarlet Witch arrive and the Avengers Assemble to sort out Kang once and for all. But Kang outsmarts them and signals his armies to begin the invasion of Ravonna's kingdom, leaving the readers once again teetering on the precipice of a cliffhanger.

For me, what was most interesting part of this issue was the way Kang was depicted as desiring something other than all-out conquest. It would be hard to imagine Dr Doom showing mercy to a region he wanted to invade simply because he was sweet on the ruler. And though this part of the story would show Kang simply trying to conquer the Princess Ravonna in the same way he had conquered countless planets before, this softer side to his character would play out more fully in the second and concluding part of the tale.

Avengers 24 opens with a slightly odd situation. Inside Ravonna's kingdom: the Princess, her father and their loyal but heavily outnumbered troops; The Avengers; and Kang. Outside the kingdom, Kang's hordes, mounting an overwhelming attack against the stronghold's meagre defences. Yet, even though it looks like the Avengers might prevail by capturing Kang, he escapes them by unleashing a cloud of poison gas and fleeing in the confusion.

Now with no leverage against Kang's invading hordes, Ravonna's generals want to surrender. But Cap gives a stirring speech, shaming the generals into fighting to the last man. Though Ravonna's troops put up a valiant fight, the invaders are soon in control of the citadel anyway and even The Avengers cannot hope to stand for long before such hopeless odds. And so Cap, Hawkeye and Scarlet Witch are dragged, bound, before Kang. Only Quicksilver remains free. Still Kang is interested only in the Princess. Again he demands that Ravonna agree to be his wife, but is interrupted by one of his commanders, Baltag, who says that according to his own rules Kang must execute all defeated leaders. The other generals all agree, and suddenly Kang is facing dissension in the ranks. His only choice now, if he is to save Ravonna, is to ally himself with The Avengers against his own troops.

With such forces arraigned against them, Kang's former followers have little chance and the battle is soon won, with Kang pledging to release Ravonna and her kingdom. But the final twist is that Baltag, still at large, tries to shoot Kang but hits Ravonna, who has thrown herself forwards to shield Kang, just as The Avengers are returned to their own time.

I'd not read this story for a few years and was a little surprised at how complex the tale is. I had forgotten how Stan had humanised Kang by giving him a genuine love interest, which I thought was pretty unusual for the time. Also, Avengers 23 marked John Romita's first work for Marvel Comics since the 1950s. The exact circumstances of how Romita returned to Marvel are related in another blog entry. Working over Don Heck's pencils, Romita turns in workmanlike, if a little blocky, delineation on the first 20 pages of the story. Many faces in the story have little Heck left in them, compared to those inked by Dick Ayers in the following issue. It was the only Avengers Romita inked in this period as he was immediately taken off the assignment and put to work on Daredevil, covering the sudden, though not altogether unexpected, departure of Wally Wood.

The next issue would line up Dr Doom as an adversary for the Quartet, which seems an odd choice, seeing as we've just had two issues of a Doom-related villain.

UNDER DOOM'S DOME

I've never really liked Dr Doom as an antagonist for anyone other than the Fantastic Four. Amazing Spider-Man 5 (Oct 1963) had the first appearance of Doom outside of an FF title, and that was my least favourite of those early Spider-Man stories.The thing is, with Doom and the FF it's personal. His sole driving ambition is to prove he's better than Reed Richards - in fact, Stan tells us that on page 2 of Avengers 25. Beyond that, he's really not a bad fella. He rules Latveria as a benign dictator ... the citizens may not have much freedom but they are, for the most part, well taken care of. So pitting him against The Avengers isn't really an ideal fit.

"Before I battle the Fantastic Four again, I must fill their hearts with fear," says Doctor Doom, as the tale opens. "And what better way to do so than by defeating another super-powered team, such as The Avengers, with the greatest of ease." That's all the rationale we get. When we cut to Avengers HQ, we're treated to another scene of Hawkeye giving Cap a hard time, which in turn makes Cap question what his purpose is beyond just being Captain America. A few days later, Wanda receives a letter from Latveria telling of a long-lost aunt. Of course, the readers are yelling, "No, don't go to Latveria!" But The Avengers seem blissfully unaware of just who runs that comic-opera european state.

|

| Political incorrectness aside, Doom's kindness here will later be tested when he has the choice of saving the child's leg or keeping The Avengers prisoners. |

On the streets, Doom's subjects quickly turn on The Avengers, so they're forced to track Doom to his castle. The confrontation is a bit by-the-numbers and all they manage to do is damage Doom's armour and escape into the countryside. Even as they do, a delegation of villagers shows up, with the child Doom was kind to earlier, asking that the dome be opened long enough for the child to leave for America where he is to receive specialist treatment that will allow him to walk again.

Hearing of the child's plight, The Avengers return to Doom's castle to force him to raise the dome. There's another couple of pages of battle and The Avengers destroy Doom's controls opening the dome so they can escape.

"Enter ... Dr Doom!" is probably the weakest of the Quartet tales, but luckily, Stan had some significant changes in mind, starting the very next issue ... with the return of The Wasp.

But before that I want to look at an aspect of Marvel's history that I don't think anyone else has mentioned ...

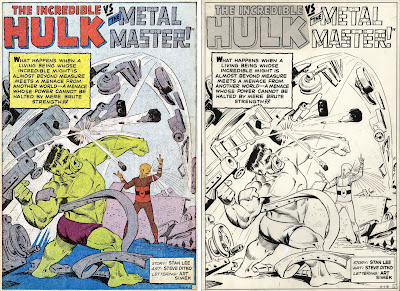

THE MYSTERY OF THE PASTEL SPEECH BALLOONS

In many of the pre-hero Marvel comics, it was quite common for the colourist - mostly Stan Goldberg, I believe - to add a yellow tint to the caption boxes in the stories. This kind of made sense, because it created a visual separation between the narrative captions and the dialogue balloons, which remained untinted. |

| The yellow tint on the caption box was very common in pre-hero Marvels. This scan is from the Jack Kirby-drawn "Menace from Mars" story in Journey into Mystery 52 (May 1959). |

But sometime during the rise of the superhero stories at Marvel, the tints on the balloons got to be pretty much random. Try as I might, I cannot see a pattern to the layout of the balloons on some pages.

It seemed that Stan Goldberg was just dropping tints on speech bubbles randomly. If it had been consistent, even within the same story, it might have been easier to fathom. But where radio balloons might be tinted pink in one story and not at all in another, sometimes the colouring on the balloons would vary even within the same page.

It's not in the least important in the grand scheme of things. In fact it's probably the most trivial of all the trivia I've covered in this blog. Mostly, I'm just curious to know if anyone else have ever noticed this and whether they've ever managed to see a pattern or a purpose to this most Marvel of practices, which died away during 1966 as mysteriously as it had arrived.

Was this a directive from Stan Lee, or was Stan Goldberg just trying to keep things interesting on the page? We'll probably never know ...

AND BACK TO THE AVENGERS

Avengers 26 & 27 (Mar - Apr 1966) would be the last of the Quartet story arcs. It featured Attuma - another old Fantastic Four foe - who was making another attempt to attack the surface world, this time with a tidal device that would submerge the continents above. |

| With the Attuma story-arc, Stan siezes the opportunity to re-introduce an old character - The Wasp - and have her act as the catalyst to bring The Avengers into the fight. |

Elsewhere, aboard a damaged scientific research vessel, Henry (Giant-Man) Pym and Janet (The Wasp) van Dyne are trying to put out a fire caused by the sudden invasion of Prince Namor, The Sub-Mariner (Tales to Astonish 78, Apr 1966). Thinking Namor is on his way to attack New York, The Wasp has to fly there to warn The Avengers. But on the way, she's captured by Attuma. The big blue despot has no idea who Janet is, but decides to hold her anyway, in case she's a spy for the surface people.

Janet manages to free herself by shrinking to wasp-size and radios The Avengers for assistance. With Hawkeye still absent, Cap, Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch race to Janet's aid. But as they approach Attuma's vessel, The Avengers' jet is grabbed from the air and brought on board the giant sub. The Avengers battle valiantly, but are eventually subdued by Attuma's forces. Then, in time-honoured super-villain tradition, Attuma insists on fighting the Avengers himself, to show his followers just how alpha mer-male he is.

Just as the battle is going against the Avengers, Wanda directs her hex at the very structure of the sub and the hull begins to break apart. The three Avengers are trapped behind a sealed bulkhead as it begins to fill with seawater. Meanwhile, back in Manhattan, Hawkeye arrives at the Mansion to find it deserted. Unable to remember how to operate the message machine, he tries to jog his memory with Tony Stark's "Subliminal Recall-Inducer". And as his sinks into unconsciousness, a sinister figure gains entry to The Avengers' HQ.

The way the Avengers storyline dovetails into the guest appearance of Hank and Jan in Tales to Astonish is pretty neat, and that kind of synchronisation would only be possible as long as Stan was writing all the titles. Tying it all together was the Sub-Mariner's nemesis, Attuma. Never quite gaining the stature of Namor himself, Attuma made many appearances in mid-1960s Marvel comics. Debuting in Fantastic Four 33 (Dec 1964), the Big Blue Meanie tried many times to take over Atlantis from the Sub-Mariner (whom he didn't consider aggressive enough) and to threaten the surface world with all-out war. Attuma would menace Giant Man in Tales to Astonish 64 (Feb 1965) and battle Iron Man in Tales of Suspense 66 (Jun 1965).

What is slightly more interesting abut this issue of The Avengers is that Stan would weave in a parallel story featuring Hawkeye and the Mysterious Villain we see in the last panel of Avengers 26.

The Mysterious Villain turns out to be former Human Torch and Spider-Man B-list baddie, The Beetle. Probably one of Marvel strangest super-foes of the period, The Beetle was designed by Golden Age Human Torch creator Carl Burgos, which might account for the slightly clunky but oddly appealing appearance of the character. In Strange Tales 123 (Aug 1964) Abner Jenkins invented a battlesuit consisting of plate steel wings which enabled him to fly. Even as a 10 year old, I was pretty cynical about the aerodynamics involved in that concept. The Beetle would go on to fight Spider-Man in Amazing Spider-Man 21 (Feb 1965)) and, later, Daredevil in Daredevil 32 & 33 (Oct - Nov 1967).

After a three-page battle, Hawkeye subdues the Beetle and learns from the message left by the other Avengers last issue that they need his help against Attuma. And at Attuma's attack sub, things aren't going tremendously well for The Avengers. Things take a turn for the worse when Quicksilver is ejected from the sub by one of Attuma's foot soldiers. Rising to the surface, the unconscious Quicksilvers awakens to find Hawkeye standing over him. The two set out to find Attuma's sub and their fellow Avengers. Meanwhile, Captain America plays the old "Your doomsday machine is a fake, Attuma" card. Dopey Attuma falls for it and explains how his tide machine works, giving Hawkeye and Quicksilver enough time to crash their craft through the side of Attuma's sub ... and all heck breaks loose.

The story closes with Attuma's sub exploding after Cap sabotages the tidal machine and The Avengers return to their HQ to find The Beetle has apparently revived and escaped. All of which leads us into the story that will signal the end of an era for Cap's Kooky Quartet.

Avengers 28 (May 1966) was a landmark issue on many levels, but the biggest surprise was the return of a superhero who'd been in limbo for almost a year. The first three pages of the issue establish that The Wasp is missing and that scientist Henry Pym needs The Avengers' help to finding her, revealing that he is actually Giant-Man. Captain America and Hawkeye have another run-in, but this time Hawkeye is markedly less aggressive and accedes to Cap's authority, setting off to fetch Henry Pym with the most muted of grumblings. Then we cut to The Wasp, who it trapped at insect-size in a tiny glass bottle.

Stan's footnote on page 2 explains that we witnessed The Wasp's escape in Avengers 26, but we actually didn't. We witnessed her radioing The Avengers from Attuma's super-sub and that was the last we saw of her. Stan covers that minor mistake with a thought balloon from The Wasp, recalling that she made it to Avengers HQ before losing consciousness. Her captor is The Collector (who would play a part in the much later 2014 Guardians of the Galaxy movie).

Something that puzzled me was The Avengers not knowing that Giant Man was scientist Henry Pym. From all those Tales to Astonish stories I read, it seemed to be no great secret that Hank was also a superhero. When the Giant-Man fan club visited Pym's lab and Janet Van Dyne was present, human-size and unmasked, it never occurred to me that Hank's identity was supposed to be hidden from the public.

Even as Hank arrives at Avengers HQ, the voice of The Collector is heard coming over the radio, ordering the team to go to a certain location if they want to see The Wasp again. At first the team are reluctant to accept Hank as Giant Man until he can give a demonstration of his powers. The catch is that after years of excessive stress on his body, Hank can only grow to 25 feet, where he must remain for 15 minutes before it's safe to return to normal height.

Of course The Avengers, plus the newly renamed Goliath, blunder straight into a trap and are easily over-powered with anaesthetic gas, and awaken trussed up like Christmas turkeys. It's not hard for Goliath to free himself, using his growing powers, then in turn break the shackles holding his team-mates. The Collector scuttles away and The Avengers give chase, but run into The Beetle, instead. Hank is left behind and has his own (huge) hands full when he encounters The Collector. Using "magic beans" from his collection, The Collector summons two giants, who are giving Hank a hard time until Wanda intervenes. The giants despatched, Hank grabs The Collector and forces him to reveal The Wasp's whereabouts. The Collector threatens to shatter her glass prison unless the Avengers surrender. Though Quicksilver manages to snatch the glass phial from The Collector, the wily villain still manages to escape using a handy "temporal assimilator" to transport himself and The Beetle away and out of danger.

The closing scene has Hank try to shrink to normal size, but after staying too long at 25 feet, he collapses unconscious, stuck at 10 feet. And that cliffhanger is where Stan leaves the readers ...

For my part, I was very excited to see Giant-Man return to The Avengers, despite the change in name and costume. Hank Pym was one of the first Marvel characters I had encountered a couple of years earlier and I always had a soft spot for Giant-Man. I think Stan must've liked the character too, certainly enough to bring him back into the Marvel mainstream after a relatively short absence.

For the preceding 11 issues of The Avengers, Stan had produced an interesting, quirky arc of stories that showed you didn't need the ability to knock down buildings with one hand to be an Avenger. It was a bold and clever move, because as much as kids enjoyed stories of super-powered heroes doing impossible things, it was also refreshing and engaging to see (almost) normal people taking on super-powerful baddies and winning, despite seemingly impossible odds. After all, isn't that what every hero - real or imaginary - is supposed to do?

It hadn't occurred to me at the time, I can now see that Stan was hoping to turn Hank Pym into the Ben Grimm of The Avengers. Where the dynamic had worked so well in the earliest Fantastic Four stories, Stan figured that he could use this book as a vehicle to explore some of those ideas further. But by issue 35, Stan was turning the title over to Roy Thomas and Goliath was given back his power to shrink to ant-size in a low-key scene on page 17 of that issue.

Over the next year and a half of The Avengers, the line-up of Captain America, Hawkeye, Quicksilver, Scarlet Witch, Goliath and The Wasp would remain pretty stable - for 17 issues - with just Black Widow as a frequent guest star, until Hercules officially joined in issue 45.

I will take a look at that period of the team, but I'll leave that till another post and another time.

Next: We've got you covered