Last time, I took a look at some of the legends that have appeared in successive histories of Marvel Comics and questioned whether they had been verified by the authors or simply repeated based on faith. As with many histories, it seems that opinion often triumphs over fact ... and fans of a particular artist or writer will insist that their hero tells the objective truth while all others lie and dissemble. But as my old friend and collaborator Phil Edwards always said, "There's three sides to every argument - his side, her side ... and the truth."

I've already looked at the oft-repeated story that Marvel Comics was limited to just eight titles a month during the 1960s (not true), that Stan Lee only got his job at Marvel Comics in 1941 because he was related to publisher Martin Goodman (not true) and that Stan Lee was the cause of Simon and Kirby leaving Captain America in 1942 because Stan snitched about their moonlighting for DC to his cousin-by-marriage Martin Goodman (no evidence to support that).

This time, I'm going to look at a few more cases where it seems to me as if the historians have gone with "Print the legend."

STAN LEE'S FIRST STAB AT GROWN-UP COMICS

To be fair to the comics historians, I should say that this myth has largely come from Stan Lee himself. As far back as Origins of Marvel Comics (Simon and Schuster, 1974), Stan had alluded to the claim that he had a revelatory moment when he realised he was fed up with hacking out copycat strips for Goodman and wanted to do something that would raise both his game and set a higher benchmark for the comic book medium.Stan expanded on the story in his autobiography Excelsior; The Amazing Life of Stan Lee (Fireside Books, 2002). "For once I wanted to write stories that wouldn't insult the intelligence of an older reader, stories with interesting characterisation, more realistic dialogue and plots that hadn't been recycled a thousand times before. Above all, stories that wouldn't hew to all the comicbook cliches of years past."

So, The Fantastic Four was born ... right? Well, not exactly, no.

All that stuff about wanting to quit the business and Joan Lee telling Stan to just write comics the way he wanted to, because he had nothing to lose, didn't result in Fantastic Four. It resulted in Amazing Adult Fantasy. At the very least, Stan was working on both simultaneously ... but tellingly, only one had the word "Adult" in its title. Also, only one promised to be "The Magazine That Respects Your Intelligence", right there on the cover. And though both sported a logo that strikingly resembled that of the hit, liberal-leaning Twilight Zone tv show, only one was an anthology of fantasy tales.

It's for these reasons that I think I can make a case for Amazing Adult Fantasy being the title Stan thought would bring the older reader to the table.

The Twilight Zone had premiered two years earlier, in October 1959, to outstanding reviews. "Twilight Zone is about the only show on the air that I actually look forward to seeing. It's the one series that I will let interfere with other plans", said Terry Turner for the Chicago Daily News. The New York Herald Tribune said it was "certainly the best and most original anthology series of the year" and Variety called it "the best that has ever been accomplished in half-hour filmed television".

From the outset, Serling's moral fables, with their liberal worldview and chilling observations about human frailty, won a strong audience following and, later, Emmy and Golden Globe awards. And when you compare the stories that Stan Lee was offering in his anthology titles, especially those drawn by Steve Ditko, you can see just how much of an influence on Lee Serling's series was.

So when Stan Lee felt he should do something more worthwhile than the kiddy-fodder he'd been filling the Atlas/Marvel comics with, it seemed natural to beef up the presence of the Serling-influenced Ditko fantasy tales by giving them their own title. So Amazing Adventures' Kirby kaiju stories gave way to the humanist fables of Lee/Ditko. I also think it's significant that Stan Lee almost always signed his stories with Ditko, but didn't much bother with the Kirby monster strips.

The only reason I can think of that Stan would later downplay the role of Amazing Adult Fantasy in his quest to bring a degree of sophistication to the four-colour comic book is that ultimately the title fell prey to poor sales and was cancelled by Marty Goodman before the new approach could establish itself. Far better to hitch your revolutionary game-changing approach to a success rather than to a failure.

I also can't help but observe that the first few issues of Fantastic Four followed the formula of the Kirby Giant Monster comics, almost as though Stan felt you just couldn't do grown-up superhero tales. Certainly issues 1, with the Mole Man's Godzilla-like subterranean creatures, and 3 and 4, with The Miracle Man's giant marquee monster and The Sub-Mariner's Giganto creature, didn't stray far from kaiju territory.

It wasn't really until Fantastic Four 8 (Nov 1962) that the tone of the comic shifted a bit and Stan made an effort to change the direction of the title. He makes The Thing less angry, the FF start calling him "Ben" instead of "Thing" and Reed begins his quest to revert Ben to his human form. Stan also gets rid of the (rather odd) Reed-Sue-Ben triangle and introduces a new love interest for Ben, Alicia, who initially resembles Sue - though that idea is also jettisoned quite quickly. For me, this is where Stan made a concerted effort to make superhero comics a bit more sophisticated than the standard superhero mags DC were putting out under the editorship of Mort Weisinger - pretty brave, considering how well the Superman family titles were selling in 1961.

And as history would show, turns out Stan was right. Once Marvel got into its stride, sales began to climb and the previously unassailable DC began their decline.

STAN LEE INVENTED THE "MARVEL METHOD"

There is a prevailing school of thought out there, especially among Kirby Kultists, that Stan Lee invented the Marvel Method (of comics writing) specifically to gyp artists out of their plotting payments. The story gets repeated over and over, but without any real evidence to back it up.I think the first hint I came across - beyond Stan's own explanations in the Marvel Bullpen Bulletins - of how comics were created during the early days was in Steranko's History of Comics, which I would have picked up around the age of 18. In volume 1, Steranko recounts how the classic 44-page battle between The Human Torch and The Sub-Mariner (Marvel Mystery Comics 8 & 9, Jun & Jul 1940) was written and drawn over a weekend.

"Carl (Burgos) and Bill (Everett) sat down at the drawing boards and composed the first two pages without having the slightest notion about the storyline. John Compton came in and began to plot out a script ... Breakdowns were pencilled as soon as page-by-page synopses were completed. Finished dialogue was written directly onto the pages, then lettered."

That process, with the art produced from a synopsis and the dialogue and captions written and lettered on the finished art sounds a lot like the Marvel Method to me.

More recently, I picked up a copy of The Best of Alter Ego, a compilation of the best articles from the pioneering fanzine of the early 1960s. In it, there was a short essay by Golden and Silver Age artist Paul Reinman, which first appeared in Alter Ego 4 (Oct 1962). Something Reinman wrote reminded me of that account from Steranko's History of Comics.

"I remember when the artists were just a page, or a few boxes, ahead of the writer. We would come in in the morning and the editor, who mostly doubled as the writer, would say 'Sit down. I'll write an outline of the plot in a few minutes.' While the artist was working on the first page, the editor broke down the rest of the story and typed it for the artist. The dialogue was not written before the artist had finished his inkings. When the artist looked at the breakdown of his story and if the box showed a lot of action he would let his drawing take up most of the space of this box: if it was a close-up or very little action, he would leave more space for dialogue. Well, that's the way it was in the beginning of comics."

Different publishers worked in different ways, but during the 1950s, when Marvel was known as Atlas and Stan Lee was Editor and head writer, the artists worked from full scripts. Joe Sinnott was a prolific artist at Atlas and described the work routine in The Jack Kirby Collector 9 (1995). "I'd go down to the city on Friday, and Stan would give me a script to take home. I'd start on Monday morning by lettering the balloons in pencil. Then I'd pencil the story from the script and ink it and leave the balloons penciled. I'd pencil a page in the morning, and ink it in the afternoon ... I'd bring the story back on Friday and he'd give me another script. I never knew what kind of script I'd be getting. Stan had a big pile on his desk, and he used to write most of the stories himself in those days. You'd walk in, and he'd be banging away at his typewriter. He would finish a script and put it on the pile. Sometimes on his pile would be a western, then below it would be a science fiction, and a war story, and a romance. You never knew what you were getting, because he always took it off the top. And you were expected to do any type of story."

The later, in the post-Atlas years, when Marvel Comics was only known by the tiny letters "MC" on its covers, Stan was still supplying full scripts to his artists. The seeds of the Marvel Method were sown when Stan began to ramp up output at the beginning of the 1960s and found he was struggling to do all the editing and scripting himself. So he began writing with his brother Larry Leiber, who was primarily an artist.

In an interview for Alter Ego Vol 3, No 2 (1999), Lieber explained how those early Marvel stories were done. "Stan made up the plot, and then he'd give it to me, and I'd write the script ... I was unsure of myself just sitting down to write a script. Since I knew how to draw, I'd think, 'Oh, this shot will have a guy coming this way... this shot we'll have a guy looking down on him,' and later I'd sit at the typewriter and type it up. After a while, I'd just go to the typewriter. I would follow from Stan's plots ... Jack I always had to send a full script to." [My emphasis.]

A few months later, dissatisfied with Lieber's scripts, Stan Lee hired some veteran scripters - Robert Bernstein, Ernie Hart and even Jerry Siegel - to cope with the load, but in the end he realised that to get the kind of stories he wanted for the fledgling Marvel Comics, he'd have to write them himself.

However, there is an important clue here to how Stan arrived at the Marvel Method. He was giving plots to brother Larry to break down into panel-by-panel scripts with dialogue and captions. I've not come across any indication that Larry had any input into the plots. It is possible that, when Stan was working with Bernstein and Hart, he did allow some plotting collaboration but, again, I've not found any statements from the participants to support that.

The next step in the evolution came when Lee rightly realised that it was the characterisation in the script - and the emotions felt by his characters - that made Marvel tales more appealing to his young audience than the old-fashioned, plot-driven DC-style stories. Stan understood that the details of the plot were the least important component. So rather than sit down with some less talented scripters and feed them plots, why not sit down with the artists, thrash out a plot, then have the artist draw it up before the dialogue was written? Pretty much a reversion to how it was done in the early 1940s.

As 1963 rolled over into 1964, it seems likely that Stan found some pencillers were better at fleshing out a brief story synopsis into a 20-page story than others. Steve Ditko appears to have been best at it, and had likely worked that way with Stan during the pre-hero years. Jack Kirby - even though he'd been used to full scripts from the Marvel Bullpen was able to adapt and add detail to the briefest of outlines. Others, like Gene Colan and Don Heck, needed more hand-holding.

What is interesting is that those who had the biggest issues with how Stan worked - I'm thinking Wally Wood, Joe Orlando and Gil Kane - were all from a background where they would be given some form of full script to work from.

Kane had worked for DC Comics most of his career, and the editors there would hold regular story conferences with the writers to create a plot, then have the scripters - John Broome, Gardner Fox - go home and type up a full script for the penciller. I'm pretty sure the writers didn't get paid for the plotting session.

At EC Comics, where Wood and Orlando cut their teeth, the discipline was even stricter. Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein would plot and script the stories, then give the boards to a letterer to ink in the captions and dialogue. Only then would the boards go to the artist, who would have to fill the pre-ruled and lettered panels with drawings.

So from Wally Wood's point of view, it may well have looked like Stan was getting him to "write" the story while taking the credit ... but that's only because Wood had never worked Stan's way before.

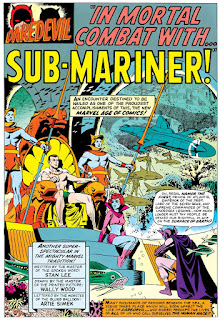

Interviewed by Mark Evanier, Wood said, "I enjoyed working with Stan on Daredevil but for one thing. I had to make up the whole story. He was being paid for writing, and I was being paid for drawing, but he didn't have any ideas. I'd go in for a plotting session, and we'd just stare at each other until I came up with a storyline. I felt like I was writing the book but not being paid for writing."

That doesn't really ring true to me. I just can't imagine Stan - the most talkative human being on the planet - just sitting and staring at Wally Wood. I rather think that Wood, like some others, is vastly overestimating the importance of the plot to a comic story. When Wood did actually write an issue of Daredevil by himself, Lee's criticism wasn't of the plot but of the lack of characterisation in the dialogue.

"I persuaded him to let me write one by myself since I was doing 99% of the writing already," said Wood in the same interview. "I wrote it, handed it in, and he said it was hopeless. He said he'd have to rewrite it all and write the next issue himself."

At that stage of the process, there was very little Lee could have done about the plot ... but he sure could fix up the dialogue.

The point is that every writer or artist has a different history and background. And each has different working habits. What works for some doesn't work for others. What drew Neal Adams to Marvel in 1969 is he'd heard that the artists worked from the slightest of plots and were free to draw the comic their own way.

So it turns out that Stan didn't invent the plot-art-script process of creating comic strips. It's a method that has been in use since the 1940s, which some artists prefer and some don't. I can see how Stan found his heavy workload - as Marvel Comics grew during the early 1960s - meant he had to find ways to get the comic stories completed faster. He tried several different processes before he hit on the one that gave him the best control over how the characters were portrayed. Because Stan was all about the characters and their emotions, just as DC were all about the plots and their resolutions, and thought characterisation was irrelevant ... And we know how that eventually turned out.

I was going to try to squeeze in an account of the 1971 "price war" between Marvel and DC and give some perspective on the sales numbers that have been quoted in a few accounts, but it's the end of the month and I just don't have the time to do it justice this month, so I'll leave it for now and try to publish the last part of this look at Marvel Myths and Legends in a week or two.

Next: The DC / Marvel Price War of 1971