BACK IN THE 1960s IT WAS THE SUPERHEROES THAT CAUGHT MY ATTENTION. First, the colourful DC heroes like Flash and especially Green Lantern. Then by the mid-Sixties, I'd focussed more on the Marvel heroes. I was aware that Marvel published other titles from the house ads in the superhero titles, but as I've mentioned before in this blog, I was never much of a fan of war comics or cowboys. It wasn't until much later in my comic collecting endeavours that I began to appreciate that Stan was a pretty good writer in almost any genre.

Marvel had three western characters that stood the test of time. I already covered Two-Gun Kid in an earlier post. Of the remaining two, Kid Colt Outlaw had the longer run, clocking up 229 issues of his own title, as opposed to Rawhide Kid, who only managed 151 issues. Kid Colt also racked up dozens of appearances in Marvel's contemporary Western anthologies, like Wild Western, Western Winners and the odd filler slot in Two-Gun Kid.

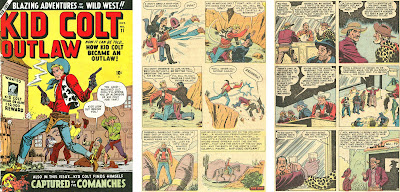

Kid Colt Outlaw arrived, full-blown, in his own title on 25 June 1948 (cover-dated August), in a 52-page mag, scripted by Ernie Hart and drawn by Bill Walsh. Who actually created the character is now lost in the mists of time, but as the back story of Kid Colt is so very similar to that of Two-Gun Kid, I wonder if Stan Lee didn't have a big hand in both.

HOW IT ALL BEGAN

Both Kid Colt and Two-Gun Kid grew up the sons of farmers. Both are pacifists who have sworn not to carry guns. And both take up shootin' irons when their respective fathers are killed. When Blaine Colt's father is murdered and the family farm stolen by crooked Sheriff Yates, young Blaine takes up his dad's six-gun to avenge his murder. But killing a lawman will never end well for the shooter, so young Blaine becomes Kid Colt, Outlaw ... always one step ahead of the posse, roaming the range and righting wrongs wherever he goes.

The earliest stories were written by Ernie Hart, which will be a familiar name to regular readers of this blog, and drawn by Bill Walsh, a veteran of the Iger Eisner shop who had largely disappeared from comics by 1953, returning to the medium for a long stint on Treasure Chest in the early to mid 1960s.

Over the next few issues many Marvel regulars contributed art to the series, with Russ Heath as the main artist and others, like Mike Sekowsky, Gene Colan and Joe Maneely, pitching in, mostly over scripts by Ernie Hart and, later, Leon Lazarus.

There was a three month break between Kid Colt 4 (Feb 1949) and Kid Colt 5 (May 1949) and when the series returned it was again as a 36-pager, though issues 9 and 10 of the book were back to 52 pages, before reverting to the standard 36 pages for the remainder of the run.

|

| Kid Colt 7 (Nov 1949) was the first to break away from the formula of the first few issues, sporting a Russ Heath cover and a book-length Kid Colt story by Hart and Heath. |

Judging from the job numbers, issues 5-8 of Kid Colt Outlaw were using up Ernie Hart/Russ Heath inventory stories and Syd Shores covers from the earlier 1948 run, though the frequency was a bit haphazard, with an inexplicable four-month gap between issues 6 and 7, then finally settling down to a bi-monthly frequency with issue 12.

The stories mostly had Kid Colt foiling schemes to take over ranches by crooked sheriffs and other unsavoury characters (well, it is a cowboy series). One notable exception was the tale "Fight or Crawl, Outlaw" in Kid Colt Outlaw 4 (Feb 1949) which had the Kid forced to take the place of a fighter in a boxing match, by Ernie Hart and Russ Heath. Curiously, an almost identical story had been published a few months earlier, "Death in the Ring" in Two-Gun Kid 3 (Aug 1948), drawn by Syd Shores. The scripter remains unidentified, but there's a good chance it's Ernie Hart - unless Stan Lee wrote the original and asked Hart to rework it for the Kid Colt story. Another Kid Colt trope was the tale in which The Kid encounters a youngster who wants to be an outlaw, for example "The Man from Nowhere" in Kid Colt 9. Then Kid Colt has the task of convincing them that the life of an outlaw is anything but glamorous. The Kid would encounter many, many rannies like this during his long run.

One odd story in Kid Colt 4 involved the Kid meeting a giant - the grandson of Paul Bunyon - in a rare fantasy-tinged tale. Pencilled by Mike Sekowsky, the scripter is unknown, though it does use fantasy tropes that wouldn't be out of place in a Stan Lee script.

One stand-out issue of the earliest Kid Colts was 7 (Nov 1949). The epic 18-page story, "Trapped Between Two Fires", had The Kid battle a ruthless Wall Street financier, The Brain, who decides to take over swathes of the West and set himself up as an absolute monarch, with an actual medieval castle. We also see the Kid travel to New York to take out The Brain's investment company that's funding his mad schemes - though I had to wonder why all the shooting didn't bring the NYPD down on The Kid. We wouldn't see its like again, and I can only surmise that editor Stan Lee experimented with this book-length format and abandoned it until it was revived with Fantastic Four 1 (Nov 1961).

Kid Colt 9 (May 1950) featured some early Marvel work by the great Joe Maneely. Maneely, had started drawing for Stan Lee's titles the preceding month, focussing mainly on western titles like Western Outlaws and Sheriffs and Whip Wilson ... and contributed art for another epic-length tale in Black Rider 8 (Mar 1950).

Maneely rapidly became Stan Lee's go-to guy for covers and over the next seven years contributed hundreds of covers to Atlas titles and dozens to Kid Colt Outlaw, including 10, 11, 12, 16, 20, 21, 40, 41, 42, 43, 47, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 60, 61, 65, 67, 68, 69, 71, 73, 75-79, 80 and 81. Jack Kirby's first cover for the title was Kid Colt Outlaw 83 (Mar 1959)

Kid Colt 11 (Oct 1950) was something of a reset issue. It presented a newly-drawn version of the "origin" story from issue 1 after little over two years, and a back-up story, "Captured by the Comanches", where an old timer sets an obsessed lawman straight on exactly the kind of man Kid Colt is ... and even though an earlier story established Kid Colt as an ally of the Comanche, in this tale he's at odds with them.

From Kid Colt 9, the old team of Ernie Hart and Russ Heath gradually gave way to scripter Leon Lazarus and artist Pete Tumlinson.

Lazarus worked mainly on Atlas western titles until the mid-1950s. He had started at Timely as a letterer, then moved into script-writing, joining the Timely staff as an assistant editor under Don Rico. When Rico (and fellow editor Ernie Hart) left the company at the end of the 1940s, Lazarus became Al Jaffee's assistant. One of the writers overseen by Lazarus was Patricia Highsmith, who would later go on to a stellar career as a novelist. Lazarus lost his staff job in January 1950, when publisher Martin Goodman decided that it was cheaper to use only freelance talent, though Lazarus continued to freelance for the company. Gradually, he transitioned away from comics to work almost exclusively for Goodman's "slick" magazines. In 1965, he made a brief return to Marvel Comics, scripting a single Giant-Man story in Tales to Astonish 64 (Feb 1965). As he explained to the fanzine Alter Ego:

"[Goodman] wasn't sold on [the Marvel Method] of doing stories [in which writers would supply artists with a plot synopsis, rather than full script, allowing artists to tell the story's visual narrative with their own pacing and details]. He became concerned that Stan would have too much leverage over him, and he worried about what would happen if Stan ever decided to leave the company. Goodman wanted other writers as a back-up in case he needed them, so he ordered Stan to use other writers ... Goodman told Stan to, 'Have Leon write stories.' Stan called me and up and asked if I was willing to come in and work there again. ... I didn't want to say 'no' because I was working for Goodman's men's magazines, and didn't want to lose the account. I only did this one story, because I wasn't comfortable with the way Stan wanted writers to work with the artists, though I see now how right he was."

|

| Leon Lazarus: 22 August 1919 - 28 November 2008. |

Howard Peter Tumlinson started selling artwork to Timely in 1949 and quickly became a frequent contributor to the western titles, drawing Kid Colt's appearances in his own magazine and in the back-up stories in Wild Western. Towards the mid-1950s Tumlinson also drew quite a few horror stories for Atlas, but dropped out of comics around that time to concentrate on book illustration.

|

| Pete Tumlison: 2 June 1920 - 5 June 2008. |

Lazarus and Tumlinson worked on Kid Colt until issue 24 (Jan 1953), when long time artist Jack Keller took over for an unprecedented 109-issue run, from Kid Colt 25 (Mar 1953) to 133 (Mar 1967).

The tone and content of the Lazarus/Tumlinson stories weren't a lot different to the Ernie Hart/Russ Heath ones. The Kid continued his travels around the west, thwarting crooked sheriffs, busting up gangs of rustlers and making hero-worshipping teenagers hate him.

With Kid Colt 25 (Mar 1953), the legendary Jack Keller took over as artist, though Lazarus would continue as scripter until Kid Colt 31 (Oct 1953) so, unsurprisingly the tone of the stories didn't really change.

|

| Three occasions in the first 24 issues of Kid Colt Outlaw where The Kid has shot a fleeing villain in the back - not really cricket, is it? |

What struck me during this period was just how ruthless Kid Colt was. Even though he was battling bad guys - and he himself was really only an outlaw due to a series of misunderstandings - The Kid would routinely shoot an escaping baddy in the back. In fact, in the first 24 issues of his mag Kid Colt killed 197 opponents by gunshot. And this doesn't count the other bad guys he despatched by knife, hurling from a height or, on two memorable occasions, causing the villains to blunder into a noose intended for The Kid.

So, although I'm not fan of censorship, I can see why some authorities might have some valid objections to some of the action in some comics of the period. And bear in mind there were other companies that published much more extreme material than Atlas/Marvel. We know that Frederic Wertham was campaigning against comics as early as 1948, when Kid Colt Hero of the West 1 debuted. So rather than rein in the killings, Marvel hired a psychiatrist to endorse the comics. From Kid Colt 2 (Oct 1948) to issue 9 (May 1950), there was a sign-off from "Jean Thompson, MD, Psychiatrist" of the New York Board of Education.

|

| For a period, all Timely/Marvel comics carried an endorsement from Dr Jean Thompson of the New York Board of Education. |

From Kid Colt 32 (Dec 1953) onwards, there would be a softening of the violence. The Kid would more regularly shoot the guns out of his opponents' hands rather than drilling villains through the heart. This might well have been because by the time that issue was going to press the Kefauver Hearings on juvenile delinquency would have been in full swing, and comics publishers deemed it wise to tone down the ultra violence. At the same time, Leon Lazarus was out as scripter - which may or may not have had something to do with the inherent violence in his stories - and another Timely veteran, Joe Gill, was in. Gill's WIKIpedia entry suggests he left Marvel for Charlton in 1948, but that doesn't appear to be the case. It seems that Gill may have left comics for a period, but soon fetched up at Marvel and Charlton in 1953, starting with a story in Kid Colt 30 (Sep 1953). Gill would write strips for Marvel in all kinds of genres, but as the 1950s wore on, he contributed fewer and fewer stories to Marvel and more and more to Charlton. Nonetheless, he continued writing Kid Colt Outlaw right up to the Great Atlas Implosion of 1957, after which the scripting was taken over by Stan Lee.

|

| Joe Gill: 13 July 1919 - 17 December 2006. |

So if we look at the next 24 issues of Kid Colt Outlaw - which takes us to the beginning of the Comics Code Approved issues of the title - there's quite a drop in the body count, where The Kid only kills 157 opponents by gunshot. And by the time we get to issue 50, just five issues into the era of the Comics Code, the body count had dropped to zero.

It's hard to attribute the toning down of the violence to any one thing. Probably the Senate Hearings and the resultant introduction of the Comics Code was a big factor, but Joe Gill's scripts may also have been a bit less kill-happy by choice. And the third factor is that with the arrival of Jack Keller as artist, The Kid seems to make far more disarming shots than kill-shots.

WHO THE HECK IS JACK KELLER?

Jack R. Keller was born on 16 June 1922 in Reading, Pennsylvania. On graduating from West Reading High School Keller starting looking for work as an illustrator and in 1941 his creation The Whistler appeared in Dell's War Stories 5, published mid-1942. From there Keller landed assignments for Quality Comics on Blackhawk, and doing backgrounds on The Spirit while Will Eisner was in the army.

"While I was still working for Quality Comics I took some work around to Fawcett and got a strip called Johnny Blair in the Air," Keller said in a 1972 interview. "It was a filler for Captain Midnight’s comic book and was an airplane strip about the Civil Air Patrol. So I did that and I also got some work from Fiction House [Wings Comics 46 (Jun 1944) to 66 (Feb 1946)]. I was very much influenced by air war which was quite a thing of the time. I illustrated Suicide Smith and Clipper Kirk. Clipper was a naval pilot and he was always on an aircraft carrier. Every time he cracked up he fell into the arms of a beautiful girl. It was always the same script every time! Suicide Smith was pretty similar only he was a marine pilot. After the war the army and navy stories disappeared and crime stories were starting to pick up. I did some work for Biro and Wood on Crime Does Not Pay. I also did some work for Hillman Publications including a strip called The Rosebud Sisters. It was about two elderly ladles, a takeoff of Arsenic and Old Lace, that got into all kinds of curious situations. So I worked on those strips and then it seemed that detective stories were fading a bit and around '48 and '49 I also did some work for a parochial school magazine called Topics. It contained comic strips that would tell the lives of priests and various types of heroes."

In 1950, Keller took a staff job in the Timely/Marvel bullpen, and began churning out horror and crime stories for Martin Goodman's very hungry comics line.

After a couple of years Keller was drawing western titles for Atlas/Marvel, at first on Wild Western, but then really found his niche as the permanent artist for Kid Colt Outlaw, where he would continue for the next 15 years, the longest run by an artist on any Marvel character.

Though never as distinctive as contemporaries John Severin or Bill Everett, Keller's work was solid, with bold figurework and deft storytelling. Looking at Keller's 1950s output now, I'm reminded at times of the Simon and Kirby work of the same period. Stan Lee must have thought so too, because not even during the early 1960s did Stan feel the need to have Jack Kirby draw a few Kid Colts to "course-correct" Keller.

After the Atlas Implosion, Keller supplemented his income by working in the auto trade as a salesman, then began drawing for Charlton, notably on the popular racing car comics of the time, like Hotrod Racers and Teenage Hotrodders.

|

| Though Keller was drawing a few westerns for Charlton during his stretch there, it was the race-car comics that he enjoyed drawing the most. |

"I was getting very wrapped up with automobile illustration," Keller told fan John Mozzer in 1972. "The racing stories that I was producing for Charlton were progressing quite nicely. Dick Giordano, who was editor at the time, offered me a very nice package if I would go exclusively with Charlton and forsake my duties with Marvel. So, after telling Stan Lee about this he gave me a counter offer to go with Marvel exclusively. I pondered the question quite a bit because they both had been excellent people to work for. I like Stan Lee very much and I also enjoyed Dick Giordano’s company. I finally decided on going with Charlton for the simple reason that the subject matter was more appealing to me. That was the sole reason. Actually, financially. Stan Lee’s offer was superior. so it was a matter of illustrating what I liked best and at that time it was auto racing."

By the early 1970s, Jack Keller had largely given up drawing comics and had returned to the auto retail business. He died in 2003, and was buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Reifften, Pennsylvania.

|

| Jack Keller: 16 June 1922 - 2 January 2003. |

BACK TO KID COLT

One thing I particularly noticed about Jack Keller's style of storytelling was that traditionally, the first page of any story in a multi-story comic would usually depict an eye-grabbing scene from somewhere in the narrative. Pretty quickly after Keller taking charge of the illustration, the first page of the Kid Colt stories would actually have the splash page as the first scene in the story. I had always thought that this had been a Jack Kirby innovation that he'd introduced with the 1960s Fantastic Four comics ... but no.

Something else I noticed about Joe Gill's Kid Colt scripts was that there were fewer instances of recycling the same old story tropes. The only two that Gill returned to a few times were the tried and trusted "Youngster wants to be outlaw and the Kid dissuades him" (six times!) and the less trusty "Kid Colt convinces the lawman chasing him that he's decent type after all" (just three instances). Larry Lazarus also used these cliches, but also enjoyed "The Kid breaks out of jail to catch the real villains" and "Kid Colt is tortured by indians".

After the departure of Joe Gill in late 1957, Stan Lee became the regular scripter on Kid Colt Outlaw, with issue 77. Though not the most reliable indicator of actual sales, the Publisher's Statement of Ownership information for 1960 has Kid Colt as the third best-selling Marvel Comic after Tales to Astonish and Tales of Suspense at an average 144,746 copies a month. Which is why Stan may have been reluctant to quit scripting the western and teen titles even as the super-hero books were burgeoning, preferring instead to hand over writing chores on Astonish, Suspense, Journey into Mystery and Strange Tales to Ernie Hart, Robert Bernstein and Jerry Siegel.

Under Stan's scripting, it was pretty much business as usual, but with just a little touch of humour. Stan would continue using the same tropes that had made the Marvel cowboys among the best-selling titles of the period, warning the occasional wayward youngster away from the outlaw life and changing lawmen's opinion of him - most of the time.

Stan also got Keller an inker ... quite why he did that I'm not sure. Maybe it was to free Keller up to take on more Charlton work, but artwork does take a noticeable upturn at this point due to the polished enhancements veteran Christopher Rule brought to the artwork.

Another innovation Stan made was to introduce an ongoing antagonist for Kid Colt. Marshal Sam Hawk was a no-nonsense lawman, who would uphold the law rather than justice. A bit like an early version of Judge Dredd. Sam Hawk would go on to appear in Kid Colt 80, 84 and Gunsmoke Western 60 (Sep 1960), then Kid Colt 98 (May 1961) and 101 (Nov 1961), then again in Kid Colt 121 (Mar 1965). I don't think The Kid ever did change Hawk's mind about him.

In Kid Colt 79 (Jul 1958), Stan and Jack Keller did a retelling of the origin, but this time changing the villain from a corrupt lawman to a local thug. The first origin story was set in the town of Purgatory, whereas Stan's retelling is set in Abilene. This was an old choice because on several occasions during the series, by-standers have remarked that they recognise The Kid because they saw him in a shootout in Abilene, so by re-tooling Purgatory as Abilene, Stan has retroactively had Kid Colt repeatedly returning to the scene of his father's murder for further gun-duels. It also suggests that Stan didn't bother reading over the file copies of Kid Colt before he took over the scripting. Perhaps he figured no one would care.

|

| For a man on the run from the law, that Kid Colt sure spends a lot of time in Abilene ... (click image to enlarge). |

Then with issue 89 it's as though Stan figured that as the fantasy titles were doing so well, he'd introduce some fantasy elements into the western titles. Kid Colt 89 (Mar 1960) cover-featured a ghost and, although it turns out to be a gang of bandits impersonating a ghost, just as The Kid is at their mercy, an unseen something scares the wits out of them. The monster Warroo, in Kid Colt 100 (Sep 1961), is just gunfighter Rack Morgan posing as a travelling magician and further moonlighting as a creature of native American legend. By contrast, the alien in Kid Colt 107 (Nov 1962) is a genuine alien, stranded on Earth when his ship is damaged by a passing comet. The friendly creature is defended from some terrified townsfolk by The Kid, and is rescued by his fellow aliens at the end of the tale. I'm pretty sure this was Kid Colt's only brush with extraterrestrials.

|

| Ghosts and monsters and aliens ... just some of the fantasy story elements that would haunt Kid Colt during the first year or two of the 1960s. |

The other innovation Stan brought to the title was the concept of larger-than-life villains. Sometimes foreshadowing later villains of Marvel's various superheroes series, Kid Colt would face off against such colourful protagonists as Iron Mask (twice, in Kid Colt 110 and 114, May 1964 and Jan 1964), The Scorpion (115, Mar 1964), The Invisible Gunman (116, May 1964) and The Fat Man and his boomerang (117, Jul 1964) - all of these would be recycled as Marvel villains just a year or too later. And although I tend to be sceptical about most Marvel prototypes, the Fat Man character was very much a forerunner of The Kingpin, who would debut three years later in Amazing Spider-Man 50 (Jul 1967). As one bystander in the Kid Colt story remarked ... "That ain't fat, that's solid muscle".

Kid Colt Outlaw 123 (Jul 1965) was the last issue to feature Stan Lee scripts and Jack Kirby covers ... and for me, this is where my interest in the title ended. Jack Keller would continue to pencil the interiors until Kid Colt 130 (Sep 1966), when the format changed to 72-page giants for three issues, but when the title returned to 12 cents and 36 pages, the scripting was by Gary Friedrich or Denny O'Neill, and Herb Trimpe, Dick Ayers and Werner Roth variously provided the pencilling.

Even though overtaken in sales by Rawhide Kid in 1963, Kid Colt Outlaw's run remains impressive. From 1948 to 1968 the title was one of Marvel's best-sellers. And even when the new material was replaced by reprint, the title continued for another 11 years, finally being cancelled with issue 229 (Apr 1979), an incredible 30 year run.

Though stories did get a bit samey - a familiar half dozen plots were dragged out and re-tooled on a too-regular basis - I still have real soft-spot for the Marvel westerns, particularly those scripted by Stan.

Next time, I'll take a look at my very favourite Marvel western character, which was essentially a revamp of a 1950s cowboy superhero.

Next: The Ghost Rider (no, the other one!)