I have no recollection of when I first saw Marvel Super-Heroes 1 (Oct 1966). And back when I was twelve, it never occurred to me to question why a comic was published. I'm sure I would have thought it was simply a companion magazine to the other giant comics I loved so much, Marvel Tales and Marvel Collectors' Item Classics. Expensive though they were at 1/6, almost double the price of a regular comic, they provided me and many other Marvel latecomers easy access to the earliest Marvel stories. I think at the time I had already picked up Avengers 2 and Daredevil 1 from one of the second-hand shops I haunted, so for me the big draw with MSH1 was the reprint of the Golden Age Human Torch and Sub-Mariner battle from Marvel Mystery Comics 8 (Jun 1940).

Ever since reading in Fantastic Four 4 (May 1962) that there had been Sub-Mariner comics in the 1940s, I'd been intrigued to know what they were like. And here was Stan showing us not only some pages from the Golden Age of Comics, but also his first text story from Captain America 3 (May 1941).

To be honest, the Golden Age was a bit of a disappointment to my 12 year old self. Even at that age, I could grasp the historical importance, but I thought the actual comic strip was crudely drawn - I mean, I thought I could have done better myself - and was badly written. Not like the Stan Lee/Jack Kirby tales I was reading in the contemporary Marvels. And from there on, I never really warmed to the comics of the 1940s.

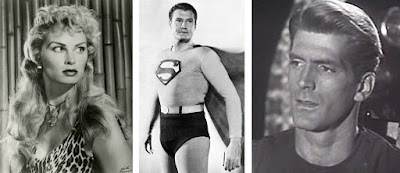

None of this explains, however, what the point of Marvel Super-Heroes 1 was. Despite promising in the small print that the title would be published quarterly, the second issue never appeared. And I didn't find out the answer to that until fairly recently. Because what we fans couldn't know was that Marvel publisher Martin Goodman had ordered Stan Lee to get a comic on the newsstands called Marvel Super-Heroes to promote the forthcoming September 1966 release of the syndicated Marvel Super-Heroes tv show.

|

| Here's one of the ads that ran in Marvel comics for the Marvel Super-Heroes syndicated television cartoon show. No sign of Daredevil here. I wonder what Stan was thinking ... |

This could have been because Martin Goodman didn't want any info about the forthcoming tv show leaked too early. Stan plugged the show in the very next Bullpen Bulletins page in the November cover-dated issues. Then, a year later, Marvel would change Fantasy Masterpieces, a title reprinting mostly Golden Age and Atomic Age Marvel characters, into a comic that would showcase new characters under consideration for their own titles. Stan called it Marvel Super-Heroes.

During the negotiations for the Marvel Super-Heroes show, Martin Goodman had held back Spider-Man and Fantastic Four from consideration, because I suppose he figured he could get a better deal for those characters if the 1966 Super-Heroes show did well. It must have worked, because in 1967, Marvel announced that network ABC would be screening Spider-Man and Fantastic Four cartoons as part of their Saturday morning show, "Hannah-Barbera's World of Super Adventure". The Fantastic Four cartoon was produced by Hannah-Barbera, and I'm presuming this made for better quality of animation than the low-budget, limited animation we got with the Marvel Super-Heroes show. I'm saying "presume" because I've never seen any episodes. That's right, the series was never screened in the UK and wasn't released on DVD, as the Hannah-Barbera catalogue is owned by Warner Brothers - who probably don't want to be promoting Marvel characters in competition with their own DC properties.

The Spider-Man half of the hour slot was produced by Grantray-Lawrence and wasn't much better quality animation than that of the MSH show they had also produced. I wrote a little about the show in an earlier blog, so I won't rehash that here ... but as with Marvel Super-Heroes, Martin Goodman hatched a plan to promote both Marvel Comics and the Marvel cartoons with a special one-shot mag, America's Best TV Comics 1 (Nov 1967).

Though it wasn't branded as such, the comic was produced by the Marvel Bullpen and featured - front and centre - a severely edited Spider-Man story (reprinting just ten story pages from Amazing Spider-Man 42) and another ten pages from Fantastic Four 19.

The rest of the comic was filled out with a Casper the Friendly Ghost reprint, and some specially commissioned strips featuring George of the Jungle, Journey to the Center of the Earth and King Kong, by various members of the Marvel art staff. Sixty-four pages of comics for 25c ... and no ads. And no Beatles, probably due to contract issues, or perhaps the fact that the cartoon feature Yellow Submarine was either under way, or about to start production, and the loveable Moptops were keeping their options open. I'm pretty sure this wasn't distributed in the UK, and I picked up my copy at a London Comics Convention some time in the late 1970s.

Around the same time, Marvel prepared another one-shot, the Daredevil Annual 1 (Sep 1967). OK, technically an Annual isn't a one-shot, but in all fairness the second (all-reprint) issue didn't appear until 1971 - well outside the fabled Silver Age of comics and therefore in my book doesn't count!

The comic essentially tried to invoke the same magic as the frankly fabulous Amazing Spider-Man Annual 1 from 1964. And to be fair, with the incredible Gene Colan artwork it almost managed it. The main story was a rattling good read at 39 pages of all-new Gene Colan art, and at the time Colan was my absolute favourite Marvel artist. Backing that up were 16 pages of pinups and behind-the-scenes explanations of how DD's billy club works, and like that.

Beyond the comics it published in 1967, Marvel was affected by other big changes in the industry. The first was that National Periodical Publications (it didn't officially change its name to "DC Comics" until 1971) was bought by Kinney National, a car park company that had money to invest. They would later also buy Warner Brothers-Seven Arts. This was important to Martin Goodman's operation because National Periodicals also owned Independent News, the company that distributed Goodman's magazines and comics ... and it was National's Jack Liebowitz who maintained the limiting stranglehold over the number of titles Marvel could put on the newsstands.

I can't be sure, but it seems pretty likely to me that someone at Kinney looked over the sales figures of Marvel and thought, "Why the heck are we limiting these guys? They could be selling millions more comics for us if we just let them!"

As mentioned at the end of my October 2019 post, according to the audited ABC magazine sales figures, by the beginning of 1967, Marvel was beginning to edge in front of DC in sales. So it's likely that the bean-counters at Kinney removed the restrictions, paving the way for Marvel's expansion at the end of 1967 and into 1968, beginning with the Marvel anthology titles Tales to Astonish, Strange Tales and Tales of Suspense.

For years I wondered why Martin Goodman structured the expansion of the anthology titles the way he did. I've laid out a plan of the 1968 expansion in the below table so you can see at a glance how Suspense, Astonish and Strange Tales were converted to single character titles.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| Tales of Suspense | 97 | 98 | 99 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Captain America | - | - | - | 100 | 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 |

| Iron Man | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Iron Man & Subby | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tales to Astonish | 99 | 100 | 101 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sub-Mariner | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Hulk | - | - | - | 102 | 103 | 104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 110 |

| Strange Tales | 164 | 165 | 166 | 167 | 168 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Doctor Strange | - | - | - | - | - | 169 | 170 | 171 | 172 | 173 | 174 | 175 |

| Nick Fury | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

In April, Tales of Suspense was retitled Captain America and Tales to Astonish became The Incredible Hulk. Now to my 13 year old way of thinking, Marvel should have put Iron Man and Sub-Mariner immediately into their own titles. But Martin Goodman was likely much more savvy when it came to newsstand distribution, so he held the Iron Man and Sub-Mariner titles back a month. I'm now guessing he did that so as not to stretch the pocket money of his young customers too thin in a single month.

However, that would have left Marvel readers without an Iron Man or a Sub-Mariner story in April 1968 ... so Goodman simply put a new comic on the schedule ... the one-shot Iron Man and Sub-Mariner 1.

|

| Iron Man and Sub-Mariner 1 had wall-to-wall Gene Colan art, so that was an excellent reason to buy it ... also the stories continued right on from Tales of Suspense 99 and Tales to Astonish 101. |

And he did that by cramming two 11-page instalments of the Iron Man and the Sub-Mariner story arcs into one regular-size comic mag. The following month, both characters would get their own titles ... but for comic readers in the UK, the spotty distribution meant that I picked up both IM&Subby 1 and Iron Man 1 (May 1968) off the same spinner rack at the same time.

Later the same year, I came across the 68 page giant Tales of Asgard 1 (Oct 1968). This simply packaged up the "Tales of Asgard" back-up strips from Journey Into Mystery 97 - 106 in a double-sized 25c package. I'm really not sure what the point of that was ... the back-up strip had been chopped out of Thor's ongoing comic with issue 145, replaced in Thor 146 with The Inhumans. When that mini-series came to an end, the main Thor strip was expanded to 20 pages to fill the comic. Was Stan - or possibly Martin Goodman - testing the waters to see if the readers wanted "Tales of Asgard" back? Certainly, Thor was the best-selling of the former anthology titles (averaging 295,000 copies a month during 1968, compared with the next best-selling, Astonish at a tad under 278,000).

Whatever the reason, the comic remained a one-shot (it was billed that way in the mag's indicia), and we wouldn't see "Tales of Asgard" again for a very long time.

That same month, Marvel published the first Hulk Special, another mag that wouldn't have a second issue - at least not for several years, and all-reprint, at that. (Edit - Kid Robson has pointed out that the second Hulk Special did appear just a year later. It just seemed a lot longer to my tweenage self.)

I won't go too much into the content of Hulk King-Size Special 1 (Oct 1968), as I covered it in some detail both in the "Messing with the Cover" entry in this blog and in the more recent Inhumans entry, just a couple of months back. The story was a mammoth 51 pages, a record I believe for a single story at the time, which left little room for any back-up features. Also, that job kept penciller Marie Severin away from the regular monthly Hulk title, opening the way for newcomer Herb Trimpe to take over, a strip he would later become inextricably linked with.

And that was pretty much it for Marvel one-shots in the Silver Age. As the 1960s drew to a close, and Martin Goodman was edged ever-closer to the door by Marvel's new owners, Perfect Film and Chemical, the company aggressively expanded the line, looking to crowd DC Comics and other competitors off the newsstands, stretching themselves thin and compromising the quality of the content in the longer term ... but that's a story for another time.

Next: Exposed - Myths of the Marvel Silver Age