At the time I was mesmerised by the idea of a blind superhero and - not knowing Wally Wood from Adam - Stan's cover blurb trumpeting the arrival of "the brilliant artistic craftsmanship of famous illustrator Wally Wood" completely passed me by. This may not have been the first time Stan puffed up an artist on the cover of one of his mags, but he'd never done it with this much hyperbole before.

However, as much as I loved the very idea of Daredevil, I wasn't mad about Wally Wood's art in this issue. Admittedly, at the time, I certainly wasn't aware of the brilliant work he'd done on the EC science-fiction titles, but my sensibilities were more in line with the work of Kirby, Ditko and Heck, and this new guy, with his tiny figures and crowded pages, just wasn't ticking any boxes for me.

WHO THE HECK IS WALLY WOOD?

Wallace Allan Wood was born in Menahga, Minnasota on 17 July 1929. As a child he devoured the great newspaper strips, like Flash Gordon, Prince Valiant and Terry and the Pirates. In love with drawing, he once dreamed he found a magic pencil that could draw anything. Wood graduated from high school in 1944 and enlisted in the Merchant Marine. In 1946, he transferred to the US Army Airborne 11th Paratroopers and was posted to occupied Japan. After demob in 1948, Wood found work as a waiter, and lugged his bulging portfolio around New York, trying to get drawing work from any publisher who'd let him in the door. |

| Wally Wood |

|

| A George Wunder Terry and the Pirates daily from 1949. This would have been the period that Wood was working as one of Wunder's assistants, inking backgrounds and perhaps lettering. |

|

| While at Fox, Wood turned his hand to any kind of comic ... romance, classics and crime.However, it wasn't long before his varied work for Fox caught the eye of other publishers in the field ... |

Very, very quickly, Wally Wood went from being a jobbing artist to a master craftsman. The speed of his improvement was simply astonishing. And even more incredibly, despite the ever-increasing amount of detail in his pages, he turned out art faster and faster. He would be one of Harvey Kurtzman's go-to artists for the new MAD comic (which would become vitally important later on in his career), where he'd craft pitch-perfect parodies of the great comics strips he'd loved as a kid, like Superman, Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon and Prince Valiant. And in his spare time, he managed to find time to draw a couple of classic comics for Avon ...

|

| Even while working almost flat-out for EC Comics, Wood moonlighted at Avon, producing high-adventure, science fiction and horror stories with equal ease. The quality never faltered ... |

- seven pages to Two Fisted Tales 27,

- cover and seven pages to Shock Suspenstories 3,

- a six-pager and an eight-pager to Weird Fantasy 13

- a cover plus an eight-pager and a six-pager to Weird Science 13.

- And, of course, four weekly eight-pagers for The Spirit newspaper strip.

His value to EC was cemented by Editor Al Feldstein, who wrote a love-poem to Wood, "My World", illustrated by Wood himself, which ran in Weird Science 22 (Nov-Dec 1953)

In his mid-twenties, Wood was having the time of his life. He was earning an eye-watering amount of money. His work jags lasted for days until he collapsed at his drawing board. His marathon art sessions were fuelled with alcohol. But he was young and his body could take the extraordinary punishment.

Even when EC crashed and burned in 1955, after the the Comics Code killed the horror books, and Bill Gaines' attempts to do the sanitised New Direction books (including Aces High, Extra, M.D. and Valor) failed, there was still MAD. Gaines turned his comedy comic into a 25c magazine, raised the page rates even higher than they were on the EC colour comics, and for the next ten years, Wood cruised straight on as MAD's star artist, winning "Best Comic Book Artist" two years in a row at the 1957 and 1958 National Cartoonists Society Awards. But even that wasn't enough ...

In 1958, Jack Kirby asked Wood to join a space-oriented newspaper strip project as inker. The strip had begun life as "Space Busters" devised by Kirby and scripter Dave Wood (no relation), but they'd been unable to find a home for the strip. Early in 1958, DC editor Jack Schiff was approached by an agent, Harry Elmlark, who was looking for a syndicated space strip for the newspapers. Kirby and Dave Wood showed Schiff Space Busters, but he wasn't that impressed. But he did encourage Kirby and Wood to take another swing at it, very likely offering some ideas of his own. The project morphed into Sky Masters of the Space Force and that was when Kirby asked Wally Wood to ink the strip.

By this time, Wally Wood was working almost exclusively for MAD, but was also providing high quality illustrations for men's magazines and science fiction magazines like Galaxy. It all went well for a while, but then Kirby had a falling out with Schiff over payments and the whole thing turned legal. So Wally Wood left them to their squabbles - and dumped Challengers of the Unknown, which he'd also been inking over Kirby - and once again concentrated on his MAD work and his science fiction illustrations. But as the 1950s drew to a close Wood was feeling restless and a bit put-upon. He was suffering from chronic headaches and was drinking ever-more heavily to dull the pain. This, coupled with the crash of Sky Masters, led to him becoming tetchy and in 1964, as his art was beginning to suffer, MAD rejected one of his strips, Wood's first rejection since around 1950. Making matters even worse, the editor who rejected his art was Al Feldstein, the same guy who'd written "My World" ten years earlier. Feeling crushed, Wood phoned the editorial offices and quit MAD.

Artist Russ Jones, who'd been assisting Wood at that time recalled in a later interview, "MAD sent Woody a rejection slip on a comic strip lampoon, and it about killed him. Yes, the job was covered in liquid paper, but it was great compared to what Bob Clarke produced. I think the guys at MAD were just kidding around, but it backfired! I stood rooted when Wally called Bill Gaines and quit. Poor Bill ... he called many times to try and talk Woody back ... but no go. Poor Wally ... he threw out his biggest client. The whole affair was sad. No winners."

With all his bridges burnt, Wood had nowhere else to go, so he returned to four-colour comics, first working for the lowest payers in the field, Charlton, on war books like D-Day 2 and War and Attack 1 (both Fall 1964), then a quick eight-pager for Warren's Monster World 1 (Nov 1964) - an adaptation of the Universal horror movie The Mummy, with assistant Russ Jones. It was at this low ebb that Wood - probably on Joe Orlando's advice - turned to Stan Lee for work and was assigned Daredevil. And that's why Stan was trumpeting the arrival of Wood on Daredevil as though it were the Second Coming ...

THE ARTIST WITHOUT FEAR

With his second job on Daredevil - issue 6 (Feb 1965) - Wood seemed to have a better grasp of what Stan Lee was looking for, but for my money, the pacing was still off. Too many pages in the story are covered in speech balloons, making me think Wood hadn't devoted enough space to the character exposition that Stan liked to include in his books. On the other hand, the action sequences were very well thought-out. Wood had wisely cut back from the amount of detail he would have included in his EC science fiction strips, rendering his fight scenes in a clean, spare style that far better suited the material. |

| Wood's work on Daredevil 6 was a slight improvement over the previous issue, but the civilian scenes were still way too wordy and the fight sequences, while well crafted lacked variety. |

When viewed as single units the Daredevil pages looked, well, same-y. Where Kirby or Ditko would mix long-shots and close ups depending on the needs of the scene and the emotion to be conveyed by each panel, Wood framed everything at the same distance.

The story itself united two b-class villains - The Ox from Amazing Spider-Man 10 & 14 (Mar & Jul 1964), and The Eel, last seen battling The Human Torch in Strange Tales 117 (Feb 1964) - with a new villain, Mr Fear, whose "fear gas" can turn anyone into a nervous wreck. It's an interesting idea, pitting The Man Without Fear against Fear itself ... but what should have been a definitive clash of opposites ends up being a fairly pedestrian filler issue. Fortunately, the title would move up a gear with the next issue.

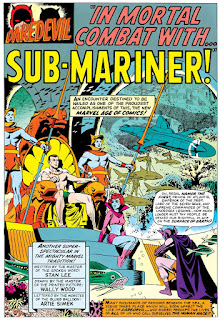

Daredevil 7 (Apr 1965) was where Wally Wood took hold of the character and began to make Daredevil his own. First, he redesigned DD's costume, using the devil part of the character's name to inspire a more streamlined approach, and giving the hero a satanic look.

|

| Daredevil 7 introduced a new costume for DD and demonstrated that the hero's will was almost as powerful as The Sub-Mariner's sea-born super-strength. |

The plot has Sub-Mariner return to the Surface World to bring a civil lawsuit against the air-breathers for depriving his people of the right to live on land. And he decides that Nelson & Murdock are the lawyers for him. But the attorneys tell him that there's no one to sue, as no individual, company or nation represents the entire human race. So Namor decides that causing a bit of mayhem and getting arrested will get him his day in court. This part of it sounds very much like a Lee plot device.

No sooner has The Sub-Mariner surrendered himself to the police and is arraigned for his crimes than word reaches him that the craven Warlord Krang has instigated a rebellion against Namor in their native Atlantis. The Sub-Mariner decides the needs of his realm are more pressing than his legal case against the humans and leaves the jail as though the bars were so much cardboard. The final battle, in which a hopelessly out-matched Daredevil fights Namor until he passes out, pretty much defined the hero's character for the next couple of decades.

But already, Wood was feeling he was being taken advantage of. The Marvel Method used by Stan, which worked pretty well for his other artists at this time, was rankling Wally Wood. He felt that he was doing at least half Stan's job without getting the credit or the payment that he deserved. Later, in an angry editorial in his self-published Woodwork Gazette, Wood described an editor he called Stanley, who "came up with two surefire ideas... the first one was 'Why not let the artists WRITE the stories as well as draw them?'... And the second was... ALWAYS SIGN YOUR NAME ON TOP... BIG."

|

| Here's something interesting ... Wood's original layout for Daredevil 7 page 4. You can see that Stan has asked for changes and the finished art is slightly different from the first pencil rough. |

Daredevil 8 (Jun 1965) introduced a new villain who, though a little bonkers, I always quite liked ... The Stilt-Man. It was also the second cover in a row to feature a newspaper headline as a way of explaining what was going on. Maybe Wood wanted that to be a thing, but it didn't pan out, or perhaps it was just coincidence.

The story has Matt Murdock engaged by a scientist who says his invention has been stolen by his employer. But as Murdock investigates the claims further, it becomes apparent that whoever has the invention is also The Stilt-Man. No prizes for guessing who the real baddie is ...

At the same time, Stan (I'm sure it was Stan) is planting seeds, suggesting that it might be possible to restore Matt's vision. In fact, Karen Page is shown suggesting that Matt consults an eminent Boston eye specialist, Dr Van Eyck. But Matt is reluctant, fearing it may compromise his powers, and Karen gets angry with him and storms out. And this sets up the situation for the next issue ...

Some changes were in effect with Daredevil 9 (Aug 1965). Even though Wood was a proven speed-demon, he's assisted on this issue by Bob Powell, with whom he'd worked on the notorious Mars Attacks gum-card series. Powell had also stepped in when Joe Orlando found himself unable to work with Stan Lee on the Giant-Man strip a few months earlier.

The plot contrives to send Matt Murdock, at Karen Page's instigation, to a European dictatorship, run by an old college acquaintance of Murdock's Klaus Kruger, the Duke of Lichtenbad, whence eye specialist Dr Van Eyck has emigrated. Once there, Daredevil is caught up in a peasants' revolt and battles Kruger's palace guards, who are all togged up in medieval armour. It's quite a fun issue, and I was always a sucker for knights in armour ...

Issue 10 brought more changes in the creative duties. With Wood increasingly disgruntled with Stan Lee's way of working, Stan credited Wood with writing as well as drawing the story, with Bob Powell providing layouts. But the way Stan did it only served to enrage Wood further.

The intro of the splash page of the issue says, "Wally Wood has always wanted to try his hand at writing a story as well as drawing it, and Big-Hearted Stan (who wanted a rest anyway) said okay. So what follows next is anybody's guess. You may like it or not, but, you can be sure of this ... it's gonna be different!" It's not the most gracious announcement I've ever seen, but there's another caption box at the end of the story that might give further insight into Stan's tone.

Apparently, after campaigning to be credited with writing Daredevil, Wood declined to script the second half of the story, leaving Stan to sort out the plot threads as best he could. "Now that Wally got writing out his system," says Stan's closing caption, "he left it to poor Stan to finish next issue. Can he do it? That's the real mystery! But while you're waiting, see if you can find the clue we planted showing who the Organiser is! It'll all come out in the wash next issue when Stan wraps it up. See you then!" So I can begin to see why there might be some growing acrimony between Stan and Wally. It's likely this is the point where Wood had told Stan that he was quitting

All that aside, Daredevil 10's not half bad ... there are a few stylistic differences, but broadly Wood does a pretty good job of making the characters all sound like themselves. And with Bob Powell doing the layouts, there's much more variety in the framing of each panel.

The plot has a mysterious character, The Organizer, recruiting a quartet of crooks and giving them animal costumes and powers to carry out a series of crimes. They are Cat-Man, Frog-Man, Bird-Man and Ape-Man. Given Stan's penchant for animal-themed villains, I suspect he may have had something to do with the casting. Curiously, though there is an Ape-Man featured as one of The Owl's henchmen in Daredevil 3, Ape Horgan, this one appears to be a different person, Monk Keefer. Even more confusingly, the Cat-Man character in this tale has the civilian name of Townshend Horgan. Was he intended to be a relative of the first Ape-Man? Or did Wood (and Stan) just get a bit muddled with their characters' names? It's the sort of continuity glitch that Roy Thomas would obsess about fixing in Marvel's later years.

There's further dissension in the letters column. One reader, Larry Brown, complains that Daredevil is turning into Gadget Man and that "all these gadgets detract from the credibility." In the response, Stan says, "Want us to let you in on an inside squabble, Larry? Sturdy Stan agrees with you - he is also opposed to so much gadgetry. But Winsome Wally really digs those hoked up appurtenances, and - being Wally's the guy who has to draw them, Stan went along with him. But we'll see how the future mail goes." Thus were the battle lines drawn. There probably wasn't any walking back from this point.

We probably shouldn't be that surprised to see Stan taking potshots on the Daredevil letters page. He must have been pretty ticked off with Wally Wood. And while it's not like Stan to be anything other than gentlemanly, he couldn't have been best pleased at Wood's attitude, considering Stan likely saw himself as trying to help out an artist he admired who was going through a bad patch. And given the circumstances, Wood's tetchiness is not that surprising either, as from Wood's point of view, Stan was getting him to co-write the comic - perhaps more than co-write - take all the credit and pay him just $45 a page. After all, at MAD they gave him full scripts and paid him $200 a page.

Daredevil 11 (Dec 1965) left Stan trying to finish a story begun by Wally Wood. He actually does a pretty fair job, though at times there looks to be a bit to much text on the page. The pacing of the hectic story is much helped by Bob Powell's layouts and pencilling, as he is more adept at bringing variety to the panel framing than Wood had been.

The issue closes with Matt announcing he's taking a leave of absence from Nelson & Murdock and Stan announcing that next issue there'll be new villains and a new artist, though he gives no hint as to who either might be.

Meanwhile, though Wood had inked this issue of Daredevil, he had already planned his escape route. A former Archie Comics editor, Harry Shorten, had approached Wood during 1965, trying to recruit him for a new venture, Tower Comics. Tower Publications had been a publisher of erotic and science fiction paperbacks from 1958, established by one of the co-founders of Archie Comics, Louis Silberkleit, and now, seeing the success of Marvel, wanted to get into the comics business. Wood called Shorten's offer "a dream set-up. I created all the characters, wrote most of the stories, and drew most of the covers. I did as much of the art as I could... But it was fun."

Wood hired old colleagues from his EC days - Al Williamson and Reed Crandell - to help out with the art, and commissioned his own wife Tatjana Wood to colour the covers. He created the characters T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents, NoMan, Menthor and Dynamo. Pretty soon, Gil Kane, Steve Ditko, George Tuska and Mike Sekowsky joined. Scripts were by Len Brown (who had worked with Wood on Mars Attacks and had helped conceive the THUNDER Agents), Larry Ivie and Wood himself. And the comics were mostly 25c, 64-page giants.

The only problem was ... the stories were just dull.

Tower Comics lasted from 1966 to 1969, when distribution problems cause Tower Publications to fold the line.

NOW WHAT?

To me it seems quite apparent that Stan was angry and disappointed with Wood's behaviour. It was highly unusual for him to contradict or criticise any of his team in print, but he did - however mildly - with Wood. You can see that, for Stan, the prospect of Wood joining the Bullpen was a big event. Though as my esteemed fellow Marvel blogger Nick Caputo mentioned in the comments last time, Stan did namecheck artists on Marvel covers before this, I think we can agree that line on the Daredevil 5 cover, "under the brilliant artistic craftsmanship of famous illustrator Wally Wood", goes a bit beyond the customary Lee hyperbole.Add to this that many have said that Stan would often give work to those who needed it, whether Stan (or Marvel) needed it. There's a story that one day during the 1950s, Marvel publisher Martin Goodman found a stack of "inventory" stories that Stan had commissioned to help out freelancers financially, but hadn't published. Goodman got angry and told Stan he had to stop commissioning until the backlog was used up. In the early Sixties, Stan had given Joe Siegel, creator of Superman, work scripting Human Torch stories for Strange Tales, but that hadn't worked out so well. By 1968, it was getting hard for Siegel to find work, so Stan hired him as a proofreader in the Bullpen.

Stan probably saw Wood as being in a similar situation in the late summer of 1964, right after Wood had recklessly quit MAD magazine. So he gave the guy a job. This wasn't just charity. Stan knew a legendary artist when he saw one. And not only did he want Wood drawing Daredevil, but legend has it that he was going to give Marvel's new Sub-Mariner strip to Wood as well. In his Alter-Ego magazine, Roy Thomas said that, “Wally was slated to go from Daredevil onto the then-up-coming Sub-Mariner solo series in Tales to Astonish [#70, Aug. 1965].”

So it must have stung that Wood was so disgruntled with Lee and Marvel from the get-go, and by the time Wood quit, I'm fairly sure Stan wasn't that sorry to see him leave.

However, in the end, it didn't work out so bad for Stan and Marvel. The very next issue of Daredevil featured the art of John Romita - albeit over Kirby layouts - and that association worked out pretty well over the years.

Next: The Fab Four