WHEN I FIRST STARTED READING COMICS IN THE 1960s, not even the writers and artists were mentioned anywhere in the DC books I cut my teeth on, let alone the editors. It wasn't until I became involved in professional publishing that I began to grasp the scope of just what it is an editor does do.

|

| My editorial life was never as glamorous or as important Ben Bradlee's, but I do love movies that depict the rigours and responsibilities of being an editor. |

Back at the beginning of the 1970s, I had an aspiration to be a comic artist. I had all the kit ... Windsor & Newton sable brushes, a good supply of india ink, pencils and erasers. And I even did the first year of A-Level Art, thinking it might be useful if I had pursued my original, more grown-up idea of being an architect. But parental pressure to take a more realistic approach to my career resulted in me concentrating more on science and finally going to City of London Polytechnic (now London Metropolitan University) to study psychology. But while there I got involved with the college newpaper, Pepys, creating logos and helping with layouts. I'd also done a couple of stints at Marvel UK as a general dogsbody during the holidays. So when my friend Dez Skinn offered me some (initially) temporary work at Top Sellers (publishers of MAD, and House of Hammer) right after leaving college, I almost bit his hand off.

|

| It was 1978. On MAD I had to anglicise the gags and have the text reset to fit in the existing balloons. Marking up type for HoH was a bit more straightforward, as we were printing articles in traditional column format. |

One of the first things I learned was how to mark up typewritten manuscripts for typsetting. Both MAD (in its speech balloons) and House of Hammer (in its articles) used typeset text (no computers back in those days), so I had to read the typewritten text through for style and errors ("subbing"), then hand-write on the instructions to the typesetter. The markup might typically look like this:

9/10pt Times Roman Med x 14ems

That just means 9 point (tall) text, in a 10 point line-space, Times Roman font, medium (normal) weight, across a width of 14 ems.

|

| A Geliot Whitman depth scale - we use the 12pt scale to measure column width. The other scales are used to count lines in a column of text. |

Subbing was another necessary skill. Reading through an author's typed manuscript, catching typing or grammatical errors, smoothing any bumps in "readability" or style to make sure the manuscript was ready for typesetting. A typesetter would "follow the manuscript out the window", so any mistakes here would need to be caught and fixed manually at galley stage.

Proofreading was something you more or less taught yourself. At the beginning I'd proof a galley and give it back to Dez. He'd glance at it and say. "You missed three typos." So I'd have to proof the galley again. Best. Training. Ever. I soon figured out how to proofread flawlessly.

Pretty soon, I learned there was more to editing than just technical stuff like markup and proofreading. Another basic thing Dez taught me was that when cover lines run over more than one line, break the text where the natural pauses fall, creating a rhythm ... so:

| Not like this | But like this |

WILD

KIDS LOCKED,

LOADED & ON

THE TOWN | WILD KIDS

LOCKED,

LOADED

& ON THE TOWN |

As MAD and House of Hammer at Top Sellers became Doctor Who Monthly and Starburst at Marvel UK, my experience and responsibilities grew. On Starburst I was commissioning articles, paginating each issue (deciding what went in the mag and where it should go) and occasionally reviewing the unsolicited submissions pile to see if any of the aspiring contributors had enough talent to make it as a professional. The other part of the job was staying in touch with the press officers at the various film companies to ensure we had a steady stream of press screening invites and movie stills. Some of those press officers - Eileen Wise at Disney and Nic Crawley at Warners - remain friends to this day.

Doctor Who Monthly I inherited from another editor at Marvel UK. It wasn't the easiest of transitions. As part of the hand-over I was given four pages of unlettered David Loyd artwork from an Alan Moore script, and I could immediately see we had a problem. The relatively inexperienced Moore had a lot of very good ideas he'd tried to shoehorn into his script, but with only four pages it was simply not possible to fit all of his captions and dialogue as written into the available panel space.

|

| Pretty wordy, eh? Yet this is what it looked like after I cut down the verbiage by about half. I added a credit for myself as Editor not because I'm an egomaniac, but to indicate that I'd heavily edited Alan's original script. |

Of course, the problem should have been fixed at script stage. The previous editor should have either got Moore to re-write, or given artist Lloyd another page or two to expand the story. But because neither of these things happened, I was lumbered with hundreds of pounds worth of script and art that was effectively unusable. I stuck the story in a drawer and held off tackling the problem as long as I could, but eventually the accountants wanted to know why all that money had been spent on a story that hadn't been used.

I called Alan, explained the problem and offered him the opportunity to edit down some of his captions and dialogue. Unsurprisingly, he wasn't much interested. The alternative was that I would do the cutting myself. Alan wasn't pleased about that either, but there was no way I was going to be allowed to shelf the story. And that was that ... I was one of the first to make the Moore sh*tlist. But to be fair, there wasn't a lot of point in him shooting the messenger ...

Recollections may vary ...

Another, slightly more serious challenge happened while I was editing the Starburst sister magazine cinema. Alan Jones had secured an interview with cult actor David Warbeck (at one stage in the running for the James Bond role). Warbeck had had a colourful career as one of the UK's most successful models (he was a Kiwi) and had a sprightly run as an actor in Italian movies. One of his roles brought him to the set of Russ Meyer's Black Snake (1973), and Warbeck recounted an anecdote he was told by the movie's producer about the time Russ Myer tried to blow up his then-wife Edy Williams' car with dynamite while she was driving it.

|

| David Warbeck in Black Snake. |

Unfortunately Meyer read that issue of cinema and pretty soon his lawyers were demanding a retraction or they would sue Marvel, Alan Jones and me, personally. For some reason, I don't think they were going to sue Warbeck, who'd actually recounted the story. Go figure. A retraction was given and all was well, but it does highlight the fact that an editor is legally responsible for everything that goes into their magazine.

And that's really the bottom line - the editor is responsible for everything that goes into the magazine.

Ultimately, it doesn't matter what the writer (or artist) wants, or thinks is right, or thinks is their right. It's the publisher's money and they - or their proxy, the editor - will decide what doesn't or doesn't fly when it comes to the magazine's content. And I've found myself on both sides of that great divide at various stages of my career.

You want creative freedom? Then you're going to have to self-publish. Even Stephen King and J. K. Rowling have editors.

So what does any of this have to do with Marvel in the Silver Age? I'm coming to that ...

INTERFERING WITH THE WORK OF OTHERS

There's a hate group on Facebook that purports to champion the rights of Jack Kirby to be recognised as the true creator of Marvel Comics. I say "hate group" because one of the conditions of membership is that you have to say something shitty about Stan Lee to be accepted. For them it's a Zero Sum Game - for Jack to be the sole creator they have to "prove" that Stan nothing more than show up to the office every day and get in the way. And, of course, that's just nonsense ...

|

| Mank's contract stipulated he was a ghost-writer, though Welles, as usual, did a lot of re-writing. Thirty years later, Pauline Kael wrote her essay "Raising Kane", claiming that Welles hadn't written one word of Kane. |

It calls to mind Raising Kane, the 1971 attempt on the part of film critic Pauline Kael to demonstrate that the real author of Citizen Kane (1940) was not Orson Welles but co-scripter Herman Mankiewicz. Despite "Mank" being given top billing for the co-writing credit, Welles was somehow conspiring to rob his co-writer of due credit. Like the principle architects of the anti-Stan movement, Kael's research consisted of seeking out sources - principally John Housman in her case - who agree with the central premise.

But as Peter Bogdanovich - who had written a ripost to Kael, "The Kane Mutiny" - stated in one television interview, "Even if Orson hadn't re-written some of the Kane script, he certainly directed it. And if that isn't enough, he's in it ... unless [Kael] thought that was Peter Lorre in bald makeup."

So, Stan-haters, even if Stan didn't plot the stories - and he's freely admitted on many, many occasions that often his artists would plot the stories and bring them in for Stan to write the dialogue - he certainly scripted them. I've seen claims that because artists indicated the dialogue in pencil on their artwork, "all" Stan did was re-write that. Except that re-writing would be outside the duties of an editor, which would normally be confined to punctuation and grammar corrections. But if the tone isn't right, or the dialogue is too wordy, or not descriptive enough it is absolutely the editor's prerogative to re-write it into a form they think is acceptable, which they may or may not take a credit for.

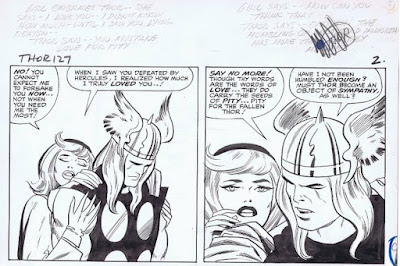

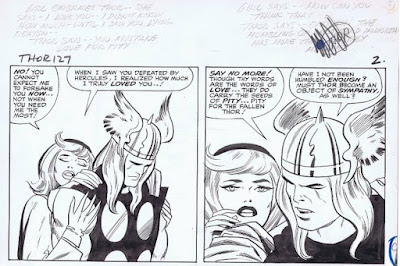

|

| Yes, Kirby has included dialogue suggestions and, yes, Lee has largely followed them. But the style and tone of the two versions are worlds apart. |

I had one case around the time I'd taken over the editor's chair on 2000AD. A writer had piled up a whole slew of scripts for a storyline I thought wasn't right for the character. I wanted to clear the decks for a new take by a new writer. Experience had told me that I couldn't just bin the scripts ... And I couldn't pay anyone to re-write scripts that were already paid for. So I had to step outside the normal duties of an editor and painstakingly re-write them into a form that would shorten the sprawling storyline yet still make sense to the readers. And I took a pseudonymous co-credit because the scripts were no longer much like how the original writer had written them, even though the plot essentially remained the same. It wasn't an ideal situation, but it did make way for a new direction for the character that I thought was more suitable.

For the most part, people who don't write fiction themselves have a very slender understanding of how a story is constructed. Particularly folks like those who hang out in the Stan-haters Facebook group. They think that the plot is the entirety of the story. But that's a hugely simplistic view. When we look back across the history of fiction, it turns out that there really only a handful of story plots. I've heard as few as three, though some pundits will push for as many as seven. They are:

The Quest: The hero sets off on a journey to obtain something or to find someone, overcoming obstacles along the way.

The Love Story: Girl meets boy, girl loses boy, girl gets boy back.

The Revenge: Villain does something horrible to the hero. Hero sets out to make the villain pay.

Author Christopher Booker also makes a case for:

Overcoming the Monster and Voyage and Return - though I'd argue that they are both pretty similar to The Quest - and;

Comedy, Tragedy and Rebirth, none of which I think you'd be likely to find in a comic, but feel free to prove me wrong.

Okay, so you pick one of the several plots that exist, then add some characters to act out your plot. Are we there yet? Well, no ... not really. Because your characters have to have character. Then they have to act according to the personalities you've given them (otherwise you're just giving readers a plot-driven story, which they won't like). And you convey their personalities and motivations with a combination of natural-sounding dialogue, and their actions (which tie back into the Plot). Then, if you're lucky and you have all those components meshed and working in synch, you just might have a working story.

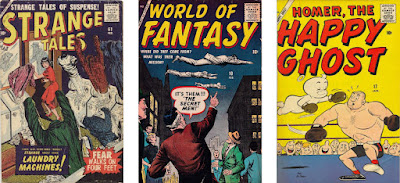

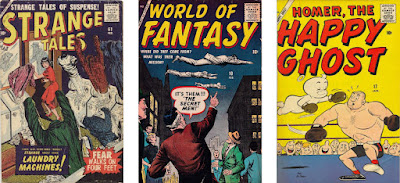

|

| Stan tried other scripters starting around August 1962, and didn't like the results: Journey into Mystery 86 (Larry Lieber), Tales of Suspense 40 (Robert Bernstein), Tales to Astonish 44 (Ernie Hart) and Strange Tales 112 (Jerry Siegel). Click image to enlarge. |

So let's allow that Silver Age Marvel's artists did do all their own plotting. But I'm still left with a conundrum, because all the Marvel books of the era sounded like they were written by the same hand. We know that Lee tried other writers from the second half of 1962, for about 15 months, and was so unsatisfied with the results that he took over scripting all the main Marvel books himself. So by the end of 1963 it must have been Stan that re-wrote any and all of the artists' supplied dialogue.

Based on this, I'd say that Stan was going beyond his duties as editor and there's a strong case for saying, yes, Lee was the scripter for these stories.

Now, I know that the Stan-haters are never going to let go of that bone. For them, Stan is the Destroyer of Careers and that's all there is. But I would say the opposite is true. But before we dig too deeply into that, let's take a look at how Jack Kirby ended up once again working for the man he most disliked.

JACK KIRBY IN THE LATE 1940s

It has always puzzled me why Jack Kirby went cap-in-hand to Marvel in the second half of 1958 to ask for work. Given his massive falling out with Martin Goodman in 1941 and his (unfounded) blaming of Stan Lee for his firing from the Timely Captain America comic, it seems odd that he would ever have anything to do with Goodman or Lee again, much less give them all "his" great ideas for a line of new superhero comics.

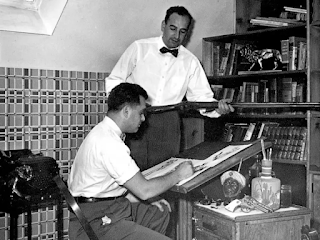

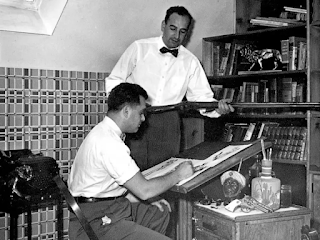

|

| Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, pictured around 1950, when they were working on Boys' Ranch for Alfred Harvey (note the prop guns). |

But let me run through the timeline of (Simon and) Kirby's work post-war and post-DC, and you'll see that some of the assertions made by Jack Kirby about his arriving at Marvel in late 1958 don't quite gel ...

|

| S&K's first titles for Alfred Harvey - Stuntman 1 (Apr 1946) and Boy Explorers 1 (May 1946). Neither comic enjoyed the massive success of Boy Commandos and Newsboy Legion. |

Even though their contract with DC ran out while they were serving in the military, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby jumped straight back to freelancing on Newsboy Legion and Boy Commandos around mid-1945. But as they were free agents they also began supplying material to Harvey Comics. Alfred Harvey was close friends with Simon and had in fact put Simon and Kirby together in early 1940. The Simon-Harvey business relationship would also be a long-term, on-and-off association that would last well into the 1960s. Harvey was known for his generosity and offered S&K a 50-50 split on all profits. The first Harvey book by S&K was Stuntman 1, cover-dated April 1946 ... quickly followed by Boy Explorers 1 a month later. Neither title lasted beyond two issues ... both were lost in the inevitable glut of comic books that appeared after wartime paper rationing ended. S&K's golden deal with Harvey ended, and the inventory material dribbled out in Harvey's other titles.

|

| Clue Comics was Hillman's answer to the hugely successful Crime Does Not Pay book put out by Gleason. S&K also created a teen book for Hillman, My Date, similar in tone to MLJ's Archie comics. |

Joe and Jack were out of work, so they looked around the industry to see what was doing well, and worked up some presentations for Ed Cronin at Hillman publications, home of Airboy. Hillman was publishing a Crime Does Not Pay knock-off called Clue Comics, so Simon and Kirby began packaging that. They also created all the material for My Date Comics 1 - not an actual romance comic ... that was some way off yet - which was cover-dated July 1947. The pair also landed a regular slot in Airboy Comics with Link Thorne - The Flying Fool.

But there was still more capacity, so S&K's next target was Crestwood, also known as Prize Comics. The pair had worked briefly for Crestwood, taking over The Black Owl and elevating it to the lead strip in Prize Comics 7 (Dec 1940). The following issue saw the debut of Ted O'Neill, but by February 1941, they had moved on, pausing to produce the first issue Captain Marvel Adventures (Mar 1941) for Fawcett before settling in to their staff positions at Timely/Marvel.

|

| After a couple filler strips and covers, S&K took over packaging the established but bland, crime-themed Headline Comics for Prize/Crestwood. |

The first thing they did for Crestwood in 1946 this time round was a story and cover for Treasure Comics 10 (Dec 1946). They followed this up with another story and cover for Prize Comics 63 (Mar 1947), presumably to demonstrate their value to the publisher. Crestwood was also putting out a so-so crime book called Headline Comics. S&K thought they could do a better job with it and took it over with issue 23 (Mar 1947) for a page rate and a percentage.

|

| Justice Traps the Guilty was another success for Crestwood and S&K, but it was Young Romance that gave them a hit on the same level as Captain America, seven years earlier. |

The changeover was a success for Crestwood, because six months later, Simon and Kirby launched their own crime comic, Justice Traps the Guilty 1 (Oct 47), at the company. But an even bigger success was just round the corner. Spotting that there were no comics for teen and pre-teen girls Joe Simon came up with the idea for a full-on love comic. Young Romance 1 (Sep 1947) literally sold out, an unheard of outcome, when comics would be doing well to achieve a 60% sell-through. Pretty soon, the title would be selling a million copies a month. The market was flooded with imitators, so 18 months later, S&K showed them how to do an imitation of Young Romance and packaged up Young Love 1 (Feb 1949) for Crestwood. That, too, sold almost a million copies.

|

| It's horror, Jim, but not as we know it. Simon and Kirby's horror titles were more spooky than horrifying, but were successful nonetheless. Black Magic lasted into the 1960s. |

Then, as horror comics were becoming popular at the beginning of the 1950s, mostly because of Bill Gaines' Crypt of Terror, Vault of Horror and Haunt of Fear books, Simon and Kirby launched a couple of (admittedly tamer) horror comics through Crestwood. Black Magic was a modest success, but its companion title, Strange World of Your Dreams was maybe just a bit too weird for the early 1950s audience and lasted just four issues.

|

| Boys' Ranch has frequently been cited as one of S&K's favourite creations. They certainly poured everything they had into it. Yet reception was lukewarm at best, and the title lasted barely a year. |

Even though they were riding high at Crestwood with their own stable of titles, Simon decided to offer their next project to his old friend Al Harvey and in the late summer of 1950, another S&K kid comic arrived on the stands, Boys' Ranch 1 (Oct 1950). Quite why Simon preferred this project to go to Harvey has never really been explained. The title only lasted six issues, but Simon and Kirby were packaging nine regular titles at Crestwood, so they weren't going to go hungry.

|

| Goodman always favoured Human Torch over the other two Timely giants, relegating Cap to a back-up strip in Young Men 24 (Dec 1953). |

Joe and Jack's last project for Crestwood before the big comics meltdown of 1954 was the patriotic character Fighting American. Over at Atlas, publisher Martin Goodman had recognised that his prize property Captain America functioned best in a war setting, and that America's proxy war against communism in Korea provided an opportunity to revive the character. So after a few adventures in Young Men, Captain America returned in his own title with issue 76 (May 1954), which kind of ticked off Simon and Kirby. So they decided to show Goodman how it should be done. But unknown to Joe and Jack, trouble was brewing ...

Because of the negative publicity from the Kefauver Hearings on comic books and juvenile delinquency, many magazine distributors were running scared. Circulations were falling and Independent News, who distributed Crestwood among other publishers, put pressure on the company owners to make the stories less sensational. It was at this same time that Joe Simon realised that he and Kirby were being cheated by Crestwood owners Teddy Epstein and Mike Bleier. They had been selling the printing plates of the S&K titles for scrap metal and not declaring it. This amounted to a $130,000 dollar shortfall in payments to Simon and Kirby, the equivalent of $1.5 million in today's money. Faced with the likely collapse of Crestwood if they insisted on getting paid, S&K accepted a good faith payment of $10k and continued packaging their titles for the company.

|

| I'm no fan of censorship, but in many ways, the publishers brought the Comic Code restrictions down on themselves. The crime books were even more outrageous than the horror titles. |

Mostly because of this - but also because many comic publishers were holding off launching new titles in the wake of the Kefauver Hearings resulting in idle printing presses - Joe Simon and Jack Kirby decided their next tranche of comic books would be published by their own company.

Leader News was the distributor for EC Comics, and they were worried that EC wouldn't weather the storm. So they offered Simon and Kirby an advance on sales. The biggest comic book printers World Color, desperate to keep their presses rolling, also gave the creators credit, so S&K were able to get Mainline Comics up and running at minimum risk to themselves.

|

| The Mainline comics mined familiar territory. Western, crime, romance and war. Can't go wrong. Note how the In Love cover re-uses the Stuntman concept of looking like a hardback book. |

Mainline Comics cautiously released their new titles a month apart, starting with the western title Bullseye 1 (Jul 1954) and Police Trap 1 (Aug 1954), both designed to not spook the retailers in the way that the EC and the Harvey books did. They followed these up with a romance title, In Love 1 (Sep 1954), and a war book, Foxhole 1 (Oct 1954). It should have been a roaring success given Simon and Kirby's talents and track record, but circumstances conspired against them.

Bill Gaines tried to continue putting out comics that complied with the Comics Code, but it just didn't work. Colour comics were a risky proposition, and Gaines abandoned the field and in July 1955 switched his Mad title to a magazine that resembled the "slicks" that Martin Goodman was putting out at Magazine Management. Leader News lost their biggest client and went under, leaving Joe and Jack without a distributor after just nine months. The last thing Joe and Jack had developed for Mainline was Challengers of the Unknown. The entire, completed first issue was shelved. Mainline ceased trading and the Simon and Kirby partnership effectively ended.

|

| After Mainline Comics folded, Jack Kirby re-focussed his energies on freelancing for Crestwood's Romance Titles, but even that was to be a dwindling market. |

Joe went to work for Harvey, repackaging old stories to make them look less like reprints and Kirby carried on drawing for Crestwood, mostly on the romance titles, and doing a little work for Harvey. But towards the end of 1956, Prize thought they could save some money by cancelling two of the S&K romance books, Young Love and Young Brides and replace them with a new romance title, All For Love, where they didn't have to share the profits.

Jack had to cast around for new work and got some assignments from his nemesis Stan Lee at Atlas, on Astonishing 56 (Dec 1956), Strange Tales of the Unusual 7 (Dec 1956) and more prominently The Yellow Claw 2-5 (Dec 1956 - Apr 1957). But working for Goodman and Lee clearly did not sit well with Kirby, so he turned his attention back to DC Comics.

|

| The last true S&K project found a home at DC Comics, two years after it was conceived. Challengers did well enough in Showcase to get its own title. |

Kirby blew the dust off the Challengers of the Unknown project and offered it to his old Boy Commandos editor, Jack Schiff. The series ran in four issues of Showcase, beginning with issue 6 (Jan 1958) and continuing through issues 7, 11 and 12. The Challengers strip graduated to its own title in April 1958. Pretty soon, Kirby was doing other stories for Schiff, on House of Mystery, House of Secrets and Tales of the Unexpected.

|

| During 1958, Jack Kirby was getting more and more work from DC. The Challengers of the Unknown book was doing well and he was graduating from mystery book fillers to doing Green Arrow for Adventure Comics. |

Then he was given the Green Arrow feature in Adventure Comics 252 (Sep 1958) and things were looking up for Jack Kirby. Around the same time, Schiff was asked by Harry Elmlark of the George Matthew Adams newspaper syndicate to suggest some comics people who could create a "space-race" newspaper strip. Schiff knew that Dave & Dick Wood had been working with Jack Kirby on a space-oriented proposal for a newspaper strip and asked to see their material. Thinking it wasn't quite right for Elmlark, Schiff suggested a slightly different approach and the result, Sky Masters, sold and ran for a little over two years. However, arguments over money began. Originally Dave Wood and Jack Kirby were to split the payments fifty-fifty (this would have been in line with how Kirby worked with Joe Simon). But Schiff wanted 5% for putting the deal together. Then Kirby wanted his share increased to 66% because he had to pay an inker out of his end (though he could have inked the strip himself). It all got a bit ugly when Schiff took Wood and Kirby to court for his share of the payments and won. Sky Masters would continue until February 1961, but working for Schiff was untenable for Kirby - he urgently needed to find another outlet.

JACK KIRBY IN THE LATE 1950s

Whether Kirby withdrew his labour from Schiff in protest or Schiff dispensed with Kirby's services is not clear, but the result was that Kirby was forced to go back to Stan Lee, looking for work. It must have been a pretty bitter pill.

|

| Pretty much as soon as his feet hit Marvel's lobby, Kirby was the go-to guy for covers and lead strips on the fantasy books, starting with Dec 1958's Strange Worlds 1 and becoming a fixture within three months. |

When Kirby washed up on the shores of Atlas Comics in July 1958, he effectively had nowhere else to go. He was doing a little work at Crestwood on the romance titles, but they too were winding down. In the June of that year, Stan Lee had lost his friend and collaborator Joe Maneely in a tragic subway accident and was barely putting out enough titles to keep even the few artists he had in work. Kirby effectively stepped into Maneely's shoes - World of Fantasy 14's cover was by Maneely, issue 15's was by Kirby - despite his vocal dislike of Stan Lee.

|

| By spring 1959 Jack Kirby had branched out into western, war and romance, starting with Gunsmoke Western 51 (Apr 1959), then Battle 64 (Jun 1959) and Love Romances 83 (Sep 1959). |

For this reason, it doesn't seem likely terribly likely that Jack Kirby arrived at Atlas/Marvel that was about to go bankrupt with a portfolio of great ideas, as he has often claimed. If Goodman was going to shut down his comics operation - remember, he had a whole other magazine division that was doing nicely, thanks - he would have done it in mid-1958, once he'd used up his inventory. But instead he gave Stan the green light to start commissioning again, so that must be taken as an indicator that the comics were still profitable.

To me, what does seem a little opportunist on Kirby's part is that he was not, given the timing, just seeking to fill the gap left by Joe Maneely, but also easing out artists like Russ Heath and John Severin who'd been drawing Marvel covers and interior art all through the 1950s.

STAN LEE IN THE LATE 1950s

The second half of the 1950s wasn't the best time for Stan Lee. His boss, Martin Goodman, had made a disastrous mistake in 1957 by dissolving his distribution company Atlas and instead signing a deal with American News Company. But when ANC was investigated for anti-trust violations, they shut down their operation leaving Goodman's Magazine Management without a distributor. Only Independent News Distribution, owned by DC Comics, would take Goodman's magazines, so the comics operation was reduced to just Stan in an office, writing and editing all the titles, and a few artists who were prepared to put up with Goodman's miserly page rates.

While there's been a lot of focus on what Stan did or didn't contribute to the writing of the stories at Marvel during the late 1950s and early 1960s, there not been much detail about what he did as an editor. In an essay for Robin Snyder's fanzine The Four Page Series 9 (2015), Ditko stated, "Writing, editing, dialogue, sound effects, captions, were all Stan's division of labour at Marvel." Later on, he would also have been writing the copy for house ads and compiling the letters columns (and the responses) during that period.

|

| There are many instances of Editor Stan Lee thinking a cover was not good enough and having the artist redraw it. Here's a few instances from the early 1960s where cover art was rejected and a new version drawn. Click image to enlarge. |

More importantly, as editor, Stan would have decided who got to draw which title. For example, when Stan wanted 57 pages of new material for the Fantastic Four Annual 1 (Sep 1963), first Al Hartley, then Joe Sinnott were assigned to Journey into Mystery for a few months. As Ditko noted in the same essay, "As I was a freelancer, Stan could, at any time, just have Sol [Brodsky] tell me I was OFF S-M, OUT of Marvel."

Ditko also described in detail just how hands-on Stan was as an editor. When he brought his pencilled pages in, "Stan and I would go over every panel; he'd note anything he didn't understand or something needed, wanted, more detail, etc. I'd mark any needed wanted changes, corrections, additions, to fix on the side of the pencilled page I was to ink. Plus, I gave Stan typewriting paper showing my rough idea of what was being said in the story broken down into panels. Stan never wanted me to write any actual dialogue or names.

|

| Even later into the 1960s, Lee would routinely decide that a cover wasn't strong enough and would have the artist redraw it. Here's a few more examples of covers rejected by Stan and their replacements. |

"The cover was always done last, and in this way: I'd take a blank sheet of paper, we'd look over the inked pages and Stan would suggest some action for the cover. I'd rough out the idea - making changes or adjustments or he'd suggest a different idea - and I would rough out, adjust, etc."

That sounds like Stan was pretty involved in the storytelling process, and very much in control of the final product, both with covers and stories. He was at least as involved as his counterparts over at DC, if not more so. And it's likely the way he worked with Jack Kirby was similar. He certainly had Jack make changes to interior pencils and would want alterations to - and sometimes even rejected - cover art.

So the claim that Stan Lee contributed nothing to the Marvel stories of the 1950s and 1960s just doesn't stack up.

|

| These teen titles had survived since the Timely Age, and astonishingly weren't culled in the Great Atlas Implosion, so they must have been selling okay. |

Earlier in the 1950s, it seems as though Stan Lee was producing full scripts. There was next to no staff in the Marvel offices and Stan didn't have the budget to use freelance writers. Quoted in the Jack Kirby Collector 9, Atlas artist Joe Sinnott explained, "I'd go down to the city on Friday, and Stan would give me a script to take home ... I'd bring the story back on Friday and he'd give me another script. I never knew what kind of script I'd be getting. Stan had a big pile on his desk, and he used to write most of the stories himself in those days. You'd walk in, and he'd be banging away at his typewriter. He would finish a script and put it on the pile. Sometimes on his pile would be a western, then below it would be a science fiction, and a war story, and a romance. You never knew what you were getting, because he always took it off the top. And you were expected to do any type of story."

|

| Marvel's long-running romance titles began in about 1950, right after Simon and Kirby launched their Young Romance comic. They too survived the implosion. |

By mid-1958, Stan would have been running out of inventory Atlas stories. Ditko started drawing regularly for Stan around that time, just as Kirby did. But when you check the job numbers of these stories on Grand Comicbook Database, you can see that the Ditko and Kirby stories mostly start with a "T", where many of the other job numbers around that time start with an "M" ... so I'm going to stick my neck out and say that the T job numbers are new material commissioned by Stan as the old Atlas inventory stock was running out.

|

| The mystery titles continued right on, though many were casualties of the implosion. Journey into Mystery had also been cancelled but was revived in 1959. Later in 1958, Goodman added the short-lived Strange Worlds book. Yes, Homer isn't a mystery title, but where else was I going to put it? |

And that was a turning point right there. Ditko was assigned stories that highlighted human foibles over spectacle, and Kirby was given widescreen kaiju stories to illustrate. I can't recall Kirby ever claiming that the giant monsters were his idea. It seems likely that Goodman saw Godzilla (1956) - or more probably walked past a theatre showing Godzilla - and said to Stan he wanted giant monster stories. Plus, by 1958, other monster movies would have been and gone in cinemas - Rodan (1957), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), The Giant Claw (1957) and Varan (1958) - and never let it be said that Goodman was too quick to jump on a trend.

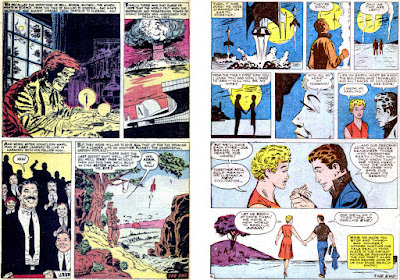

|

| Spoiler alert! Stan Lee would often recycle stories for the early Marvel fantasy titles. The fact that Stan was still giving scripts to Ditko to draw debunks the idea that Ditko was writing all his own fantasy stories during this period. |

And I don't think Ditko can take all the credit for the quieter, more humanistic stories he was drawing. There's a story in Strange Worlds 1 (Dec 1958), "I Am the Last Man on Earth", drawn by Don Heck which was retooled as "A Thousand Years Later" in Strange Tales 90 (Nov 1961), credited to Lee and Ditko. So even in 1961 Ditko was drawing from scripts given to him by Stan Lee.

|

| War books were a massive part of the Atlas line-up, yet just these titles survived the Atlas meltdown. Goodman wouldn't add another war title until Sgt Fury, some five years later. |

Of course none of this is just black or white. I'm sure both Ditko and Kirby were adding details of their own to the stories they were drawing. Stan has said as much himself, and as these two artists in particular showed strong story sense, it would have been logical for Stan to give them freer and freer rein, and to keep assigning them stories that made best use of their individual skills.

|

| Just about all the western titles survived. except for Rawhide Kid. That one was revived in 1960, with Kirby on art chores. |

In 1959, despite having only minimal presence in the Q1 cover-dated Marvels, Stan Lee assigned 36 covers out of the 90 comics published that year to Jack Kirby (and, by contrast, just four to Steve Ditko). The monster books were proving popular, because Martin Goodman had Stan add two new fantasy titles in 1959, Tales to Astonish and Tales of Suspense.

|

| As the 1950s drew to a close, Goodman was adding more monster books, mostly spearheaded by the Kirby-drawn epics. They would be the backbone of the evolving Marvel Comics into the 1960s. |

Towards the end of 1959, both Astonish and Suspense became monthlies along with Journey into Mystery and Strange Tales. The effect was that in 1960, Kirby produced 58 covers out of 103 comics published (Ditko just one). In 1961, that would rise to 73 covers from 119 comics (and four by Ditko). The trend was definitely upwards, as Kirby produced a larger and larger proportion of Marvel's output.

So the nascent Marvel Comics wasn't struggling for sales at this point. In likelihood, it was Stan's canny editorial instinct to feature the art of Kirby and Ditko that was boosting the fortunes of the monster books, as well as what he was bringing to the enterprise with his friendly, informal editorial tone - which was a big change-up from the slightly po-faced DC Comics - and his dialogue, where the characters actually spoke like real people.

|

| Left to right: Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in happier times at the Cartoonists Society in 1966 - I've not been able to identify the other two, but the man standing might be Carmine Infantino. I have no idea who the chap with spectacles is. |

And far from destroying Jack Kirby's career, Stan Lee gave him a much needed second chance and, further, promoted him as the chief artist for the entire Marvel line which, within a few years, was outselling DC.

So, that claim that Jack Kirby rocked up to Atlas/Marvel which was about to go under and gave them the ready-made books Fantastic Four (whether inspired by the Simon and Kirby project Challengers of the Unknown or not), Ant-Man, Thor, Hulk and even Spider-Man is simply not true.

But the question that some "fans" are incapable of letting go of - and argue endlessly over - is, Who did what during the formative years at Marvel? Yet I don't think it's a hugely difficult question.

|

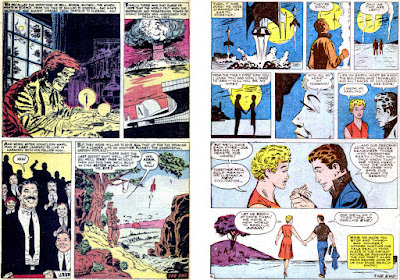

| Stan's voice - his style of writing - is all through the Marvels of the early to mid 1960s. You'll see it in the captions and dialogue balloons in the stories, on the letters pages and in the Bullpen Bulletins. Click to enlarge. |

Stan Lee was a Big Picture guy. As Editor, his job was to ensure the quality of material that went into Marvel Comics was of a certain standard. And that went beyond just the comic strips. Stan also created the Voice of Marvel ... the slightly irreverent, sort of cool-sounding uncle. He made sure that the stories and editorial pages all appeared to have been written by the same person, and made us kids feel like Stan/Marvel was our pal. And that the rest of the Bullpen were our pals, too. It's extremely likely that Stan also pitched in loads of ideas for the stories. We know that Stan loved villains named after animals and there's many, many examples of those in the Marvel stories of the early 1960s. And finally, the other job of the editor is to act as an ambassador for - and the voice of - The Brand. And we know he certainly did that. Just about all the references to Stan being "the creator" of Marvel Comics are almost always down to lazy or indifferent journalism. Reporters don't care about - nor believe their readers care about - the minutia of who does what at a comic company most of the audience have never heard of. So most of the stuff Lee is pilloried for, even after his death, was pretty much out of his control.

|

| Jack's voice is quite different in the comics he wrote the captions and dialogue for other comics around the time he was beginning to contribute to Marvel Comics. But when he got to the Fourth Worlds books of the 1970s, his writing style took on a different flavour. |

On the other hand, Jack Kirby (and Ditko, to some extent) was a details guy, who never really saw or cared about the Big Picture. It never occurred to Jack that Stan was taking care of Business at a much higher level, by editing Jack's scripting suggestions to bring them into line with the Marvel style, a style that spilled over into the responses on the letters pages and later, the Bullpen Bulletins. You can tell that Jack wasn't a Big Picture kind of creator, because the Fourth World stories that he did for DC in the early 1970s - where Jack was editing his own material - were a pretty chaotic offering. A bunch of terrific ideas not very well tied together and often abandoned before they were properly explored. And rereading some of those DC stories recently, I realised that, for all Jack's disdain for Stan Lee and the Marvel style, he was actually trying to imitate Stan's voice in the scripting of those books. Just compare any pre-Marvel 1950s work that Jack says he scripted with the Fourth World captions and dialogue and you'll see what I mean.

I really don't get why Stan Lee has been singled out for such vilification by a certain type of comic "fan". Goodness knows there are other, more unpleasant, personalities scattered throughout the history of comics. And focussing on what Stan did or didn't create within the Marvel comic stories is to completely lose sight of the real reasons for Marvel's 1960s success. What we fans - who were actually there at the time - bought into was the overall Package. Marvel wouldn't have worked without the great stories. And it wouldn't have worked without the supporting framework of the letters pages and Bullpen Bulletins, which reinforced the Voice of Marvel in our heads. If you find that Stan's voice doesn't resonate with you now, well, that's because he was a product of the times and you really had to experience it In Context during the period in which it was created. And if you still don't get it, just accept that it was never intended for you ...

Next: Invasion of the floating heads